Digitizing democracy: Former Estonian president on how e-government saved a struggling country

IN BRIEF

- For Estonia and its tiny population of about 1.5 million, size had always been a source of anxiety. Yet here was a solution: Through digitization, Estonia could dramatically increase its functional size, if not its numerical size.

- The failure of the largest — and richest — Western countries to proceed with digitization amazes me; they seem paralyzed by an irrational fear of a digital identity. The U.S. Department of Defense introduced two-factor authentication for its employees 12 years after Estonia did for all its citizens.

- The biggest issue governments face in digitization is political will. It is easier and politically less risky to continue to live in the slow and inconvenient world of paper than in the digital world.

Toomas Ilves was president of Estonia from 2006 to 2016. He is renowned for making Estonia one of the most digitally advanced nations through innovative policies that invested heavily in the future. He is recognized as a global public sector digital transformation pioneer. Born in Sweden to Estonian refugees and raised in the United States, Ilves moved to Munich in 1984 to work for Radio Free Europe. He served as Estonia’s ambassador to the United States and Canada as well as Estonia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, successfully steering Estonia into the EU and NATO in 2004. Since leaving office in 2016, he’s been chair of the World Economic Forum’s Global Futures Council on Blockchain Technology and speaks to world leaders about the digitization of government and public services.

The need to digitize Estonia became clear to me in 1993—a year and a half after Estonia re-established its independence after 50 years of foreign occupation that left the country mired in poverty and backwardness. I believed digitization was ultimately the key to national development, both economic and social, of an impoverished country. Secondly, I realized that digitization, if done right, could be the great equalizer. It could help overcome the inherent problems of scale, or lack of it, in a rather small country, even by European standards.

The development aspect was simply a result of the damage done by the half century of military occupation of Estonia by the Soviets and Nazi Germany. Between mass repressions, harebrained economics and the suppression of initiative and freedom, countries throughout the communist bloc had stagnated, falling ever more behind as the liberal democracies of the West raced ahead. The newly democratic countries found themselves little more than developing countries when they re-emerged between 1989 and 1991.

Economic realities

The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe (Volume 2) contains a bar graph showing that in 1938, the last year before the onset of World War II, Estonia had a higher GDP per capita than Finland. In 1992, the first full year after the re-establishment of independence, Estonia’s GDP per capita was $2,800 U.S. dollars (USD). Our Northern neighbour was $23,800 USD, eight times higher.

Not only did the problem lie in a poor economy, low wages, and all of the unbuilt or shoddy, substandard infrastructure that was the legacy underdevelopment under Soviet occupation, Estonia also faced, like all undeveloped or developing countries, a particularly acute form of Zeno’s paradox of the race between Achilles and the tortoise. Whenever Achilles reached where the tortoise was, the tortoise had moved ahead. This is the problem poor countries face with economic growth. A spectacular annual growth rate of, say, 10% in Estonia would increase the country’s GDP per capita just $280 USD, while an anaemic 2% growth rate in Finland would yield an increase of $476 USD per capita.

While Western and Northern Europe had in the intervening half century continuously grown by leaps and bounds and led Eastern Europe by decades, occupied Estonia had remained stagnant. The question was, how could a poor, underdeveloped country grow quickly? How could Estonia level the playing field? How could it make up for a 50-year disadvantage?

The solution became apparent to me in 1993 when Mosaic, the first web browser, was introduced while I was Estonia's ambassador to the United States. Sir Tim Berners Lee had invented HTTP four years earlier, yet it was difficult to use. But when I bought (yes, bought!) Mosaic’s five floppy discs from my local Radio Shack in Washington, DC and uploaded them to my computer, I discovered the World Wide Web—and a new world, although at the time still limited, opened up for me.

Between mass repressions, harebrained economics and the suppression of initiative and freedom, countries throughout the communist bloc had stagnated, falling ever more behind as the liberal democracies of the West raced ahead. The newly democratic countries found themselves little more than developing countries when they re-emerged between 1989 and 1991.

An opportunity emerges

Far more important, however, was the realization that the World Wide Web had arrived and brought with it the opportunity for a country like Estonia to compete on a level playing field. The internet was so undeveloped at the time, but it had so much potential. So what if the U.S. or Germany were criss-crossed by eight-lane interstate highways and six-lane Autobahns and modern infrastructure? In 1993, all of us stood at the same starting position when it came to the internet. This was the moment when I began to press the Estonian government to pay serious attention to digitization.

A second source of inspiration to push the government to invest in digitization came from a book by Jeremy Rifkind, The End of Work, which argued that computerization would cause wide-spread unemployment when computers would eventually do the work of humans. Rifkind wrote of a Kentucky steel mill, which before automatization employed some 12,000 people. After automatization, Rifkind says the plant needed only 120 employees to produce the same amount of steel.

While this indeed may have been a problem in some sectors in the U.S., for Estonia and its tiny population of about 1.5 million size had always been a source of anxiety. Yet here was a solution: Through digitization done properly, size could become far less relevant a factor. If it digitized, Estonia could dramatically increase its functional size, if not its numerical size.

Fortunately, and promoted by then minister of education, Jaak Aaviksoo, the government adopted the Tiger Leap program, meant to bring access to computers as well as connectivity to all school districts. It launched in 1996, and by 1998 all schools in Estonia had computer labs and were already online. As the internet spread through societies and countries around the world, it had become clear to Estonian IT thinkers and developers that if we wanted to make the internet more than a place to shop from home, the system needed to be far more secure and manageable to the average Estonian.

Security, security, security

Obviously, the first issue was security. There’s a 1991 New Yorker cartoon where a dog sitting at a computer says to another dog, “On the internet, no one knows you’re a dog.” Already in the late 1990s, the standard e-mail-address-plus-password login system used to this day in most commercial online transactions was understood to be insecure and thus insufficient for any government or public service functions. Instead, we would need to offer two-factor authentication and end-to-end encryption, tied to a population registry that would ensure each person had a unique online identity. As a result, no one could impersonate you and you could trust the site you connected to.

for Estonia and its tiny population of about 1.5 million, size had always been a source of anxiety. Yet here was a solution: Through digitization done properly, size could become far less relevant a factor. If it digitized, Estonia could dramatically increase its functional size, if not its numerical size.

A second security issue was database architecture. Long before the 2015 Office of Personnel Management hack in the U.S. that saw the records of 23 million past and present employees, all stored in a single database, siphoned out by a foreign actor (including addresses and even the psychological profiles of CIA employees), Estonia opted for a distributed data exchange layer created at Tartu University. We call it the X-road, and it allows for data exchange between databases—regardless of format, platform, operating system or language—safely and securely as each transaction requires secure identification and/or authentication, with all transactions logged. The X-road is currently used in some 25 countries around the world today. It is an open-source platform that the Estonian government gives away for free to other governments to use and is now administered by an international non-profit called Nordic Institute for Interoperability Solutions (NIIS).

A final security aspect of the Estonian system deals with data integrity. While attention in digitization has been focused almost exclusively on data privacy, a far more important security issue is data integrity. If someone accesses and publishes my blood type, private correspondence, or my bank account, it is a violation of privacy, embarrassing perhaps but not dangerous. If someone alters my blood type record, correspondence or bank account, it is a violation of data integrity and can have fatal consequences. This is an aspect of digitization too few governments have addressed, unfortunately. Since 2008, all critical national and private data in Estonia (for example, healthcare records, court proceedings and property registries) have been on a permissioned blockchain using Keyless Signature Infrastructure, or KSI.

E-government problems…and solutions

The failure of the largest—and richest—Western countries to proceed with digitization amazes me. This was most starkly brought home to me after leaving office in 2016, when I moved to Stanford University to what is considered the capital of IT, Silicon Valley. Within a short drive from my office, you could find the headquarters of Tesla, Apple, Google, Facebook, YouTube and other billion-dollar companies.

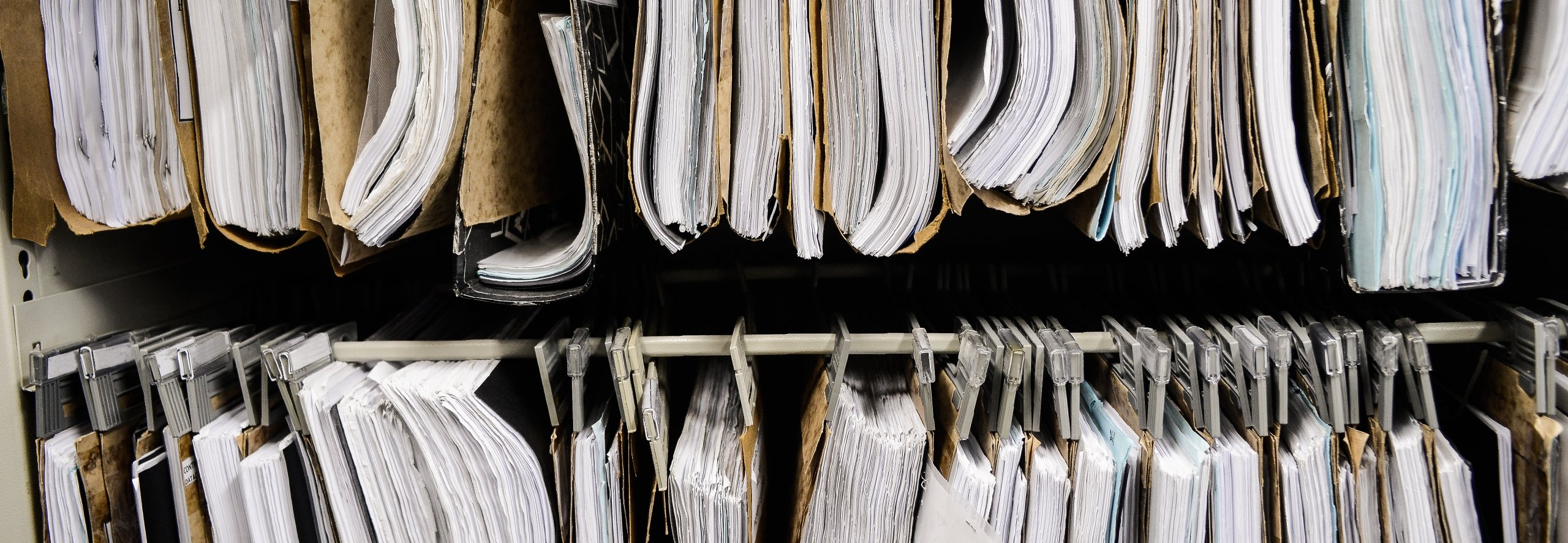

Yet, when I tried to register my daughter to go to school, I found myself back in the paper world of the 1950s. I needed to take my electricity bill, both of our passports, something called a DS-2019 form certifying that I taught at Stanford, and my daughter’s paper vaccination certificates. After driving to the Board of Education headquarters, taking a number (literally), and waiting for 20 minutes, I was finally called to register her. The woman took all the papers, photocopied them for some fifteen minutes, returned all the documents and proceeded to fill out some forms by hand, taking all the relevant information from the photocopied documents.

This, in the citadel of the digital world in one of the wealthiest countries in the world. In Estonia, this would have taken 30 seconds. Why is this?

Americans are feeling increasingly “concerned, confused, and feeling lack of control over their personal information,” a recent Pew Research Center study concluded.

The first answer is fear of digital identity. For some reason, the U.S., like Germany, Japan and the UK, seems paralyzed by an irrational fear of a digital identity. People have driver’s licenses, social security cards and any number of other identity documents but for some reason, the government does not offer secure digital identities, even 20 years after Estonia pioneered the effort. (The U.S. Department of Defense introduced two-factor authentication for its employees 12 years after Estonia did for its citizens.)

Which gets to the biggest issue governments face in digitization: political will. It is easier and politically less risky to continue to live in the slow and inconvenient world of paper than in the digital world. After all, if you have never experienced the alternative, why change? As long as governments are afraid to offer citizens a secure digital identity, they will remain stuck in the previous centuries where only paper mattered.

Another obstacle to overcome: Thinking hardware is digitization. When a country does decide to digitize its government and public services, leaders too often think it is merely a matter of buying stuff: computers, servers, data banks and more. Just let some engineers hook it all up, and we’re digital. No! That is simply the hardware of the digital world.

If you want to digitize how the government serves its citizens, you need to think of the software, both literal and figurative. Laws are the software of society. So is the culture. How do you match up your digitization efforts with your legal system or with the cultural assumptions of your populace? What information should be private (medical records), what can be semi-private (tax records in your home country), and what can be public (property records in Estonia)?

Not a one-size-fits-all approach

Digitization is not a one-size-fits-all process. Advisors and experts may tell you that you need this kind of system or software, but digitization is never a turnkey project where all the work is done for you, as if you were building a bridge or a tunnel. It requires the active participation of all the key stakeholders—political leaders, lawmakers, public servants—to ensure the effort is appropriate for the culture and legal system of a country. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Finally, to effectively digitize a country, leaders need to realize how revolutionary it can be. Digitization will completely re-order how governance works as well as how to think about government. For as long as humans have lived in states, bureaucracies have been needed to run them. Yet, since bureaucracies (or just “governance”) were invented some 5,000 years ago, they have always operated as a serial or sequential process: A paper (or papyrus or parchment) is filled out, handed in, scrutinized, registered and approved…or not. And then proceeds to the next office.

For some reason, the U.S., like Germany, Japan and the UK, seems paralyzed by an irrational fear of a digital identity. People have driver’s licenses, social security cards and any number of other identity documents but for some reason, the government does not offer secure digital identities, even 20 years after Estonia pioneered the effort.

With the digitization of governance and government services, the mechanisms of running a country can be made a parallel process whereby the steps necessary to run the country occur simultaneously. Just to give one example: When a child is born in a paper-based society, it is typically up to the newborn’s parent to run a gauntlet of registering the birth, getting a birth certificate, obtaining health insurance, etc. In parallel processing, all of this can be done in one step since all these processes occur simultaneously.

Or to take a more odious example, there is no need to get one’s employer to mail you a copy of your annual wages or to calculate your deductions based on the number of children you have. All of this can be done more efficiently with digitization, leaving citizens to pursue more productive activities while the government itself works more efficiently, thus saving the tax-payer money.

And who wouldn’t want more efficiency and additional cost savings? In Estonia, we realized both cost-saving and time-saving for both citizens and government employees. We also saw an uptake in the use of services by citizens, including our e-voting system. In the last parliamentary elections, more than half—53%—of votes were cast electronically. Digitization strengthens democracy; we expect that number to grow over time.

We’re long past the point where digitization makes sense and are at a moment in time where it is essential to provide the services that are required in the modern world. When it comes to e-government, it’s time for the rest of the world to catch up to Estonia. The countries that do digitize their systems and services—and do it correctly—will realize the benefits and efficiencies all citizens deserve.

In the last parliamentary elections, more than half—53%—of votes were cast electronically. Digitization strengthens democracy; we expect that number to grow over time.