Humanity in the age of the metaverse with CJ Casciotta, founder of Reculture

IN BRIEF

- "We’re in this weird stage where we’re doubling ourselves as people. It started with personal branding. You can have your real self and then your personal brand that you highlight and showcase. There’s a danger in the metaverse of not recognizing that there’s a difference between our ordinary selves and the versions that we blow up through a profile or an avatar."

- "What I’m calling for is a little bit more forethought so that we’re not late to the game, whether we’re a business, whether we’re a government entity, and we’re not retroactively going, 'Oh, my gosh. I wonder what happened. I wonder why this is such a big issue.' It’s a crisis and it needs to be thought of as one."

- "Genuine human interaction, what I call ordinary human interaction, a break in the automation change, is in fact a competitive advantage. Customers don’t want to go through an automated phone process that gives them seven different prompts before they actually talk to a real person."

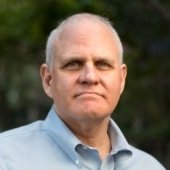

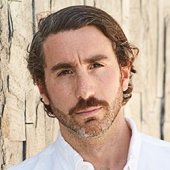

Joe Kornik, Editor in Chief of VISION by Protiviti, interviews CJ Casciotta, founder of Reculture, a messaging and production studio, and author of the forthcoming book The Forgotten Art of Being Ordinary: A Human Manifesto in the Age of the Metaverse, about the importance of keeping it real in the age of virtual worlds, and the business advantages of doing so.

In this interview:

1:05 – What is Reculture?

3:10 – A human manifesto in the age of the metaverse

6:15 – A crisis as serious as climate change

9:10 – Avatars vs. humans

11:45 – Generational divide

12:45 – What’s a business leader to do?

15:30 – Optimism about the future

Humanity in the age of the metaverse, with CJ Casciotta, founder of Reculture

Joe Kornik: Welcome to the VISION by Protiviti interview where we look at how big topics will impact global business over the next decade and beyond. I’m Joe Kornik, Editor-in-Chief of VISION by Protiviti. Today, we’re talking about the Metaverse, or more specifically, how we can maintain our humanity amid all this technology, and what happens if we don’t. To do that, I’m joined by CJ Casciotta, founder and president of Reculture, an agency specializing in messaging strategy and media production, where he's advised presidential campaigns and worked with global brands, including MGM Studios, Delta Airlines, Sesame Street, and the United Nations Foundation. His next book, The Forgotten Art of Being Ordinary: A Human Manifesto in the Age of the Metaverse, will be released in the fall. CJ, thank you so much for joining me today.

CJ Casciotta: Thanks for having me.

Kornik: CJ, I just mentioned the company that you founded, Reculture, in that intro. Can you tell us a little bit about that company and what its goals are and its visions?

Casciotta: Yes. We’re a messaging and production studio. Really, we’re in the reminding business. I think when you deal with words and pictures, we’re all talking about these advancements in automation with ChatGPT and DALL-E, and it’s an interesting time to be in the business of words and pictures but we like to say that we’re in the reminding business where, as people are learning to work alongside and work with these automated processes, I think it’s more important than ever for the workforce to be reminded of what it means to be a flesh-and-blood human being.

The best way that’s always been done throughout history is homemade stories made by humans. So, whether we’re helping a company craft their purpose in a way that’s genuine and authentic to the people they’re trying to serve, whether that’s internal or external or both or—we’re shaping that purpose and transforming it into a story via a visual or audio medium, like a podcast series or an animated production. We’re really in the business of reminding people why they get up in the morning, who they are in a season where I think you’re going to see—well, you’ve already started to see—this relationship between automated everything and AI everything and worker burnout and this realization that “Maybe I lack purpose and I don’t know what my purpose is” or hyperpolarization, all of these things that are threatening our society right now, I think one of the antidotes to that is storytelling that reminds us why we’re actually here on the planet, why we get up to go to work and do things that matter.

Kornik: Right. So interesting. I know that you’re working on a book or you finished a book that’s due out in the fall, right? Can you tell me a little bit about that book? I love the title, right, The Forgotten Art of Being Ordinary: A Human Manifesto in the Age of the Metaverse. I mean it totally speaks to me because we’ve been focused on writing about the metaverse now for several months and a lot of that focus is on the technology obviously—and some of it has focused on the humanity, but I think not enough. Can you unpack that a little bit for me and talk a little bit about the themes of the book and some of the highlights?

Casciotta: Yes. I’m a media guy, right? I’m somebody who’s done this kind of work for a good decade or so now but I’m not a social scientist. I’m not necessarily a researcher per se. So, I’m coming at the metaverse in this whole conversation from a media perspective. What I’ve noticed is—and I’m sure everybody’s really noticed—is that we’re in this weird stage where we’re doubling ourselves as people. It started with personal branding. You can have your real self and then your personal brand that you highlight and showcase. There’s a danger in the metaverse of not recognizing that there’s a difference between our ordinary selves and the versions that we blow up through a profile or an avatar.

It’s not to say that we should fear technology or we should fear the metaverse or—VR for instance, we’re working with a health tech firm doing a bunch of production stuff from them and storytelling from them and they’re really excited because they are developing these virtual reality technologies where doctors are able to practice in VR and save lives without actually having to work on a cadaver—not to be blunt and stuff—but when you cut up a—that’s amazing. It’s an amazing use of technology. But if that doctor were to turn around and think that “Well, I’m saving lives in the metaverse." To have that—to walk around with that notion that they are actually doing—that is the thing to be done versus taking that, applying that to real life, then obviously, that would be a big problem. I know that’s a funny obtuse example but that’s what kids are growing up thinking about right now. Kids have that confusion. It’s exactly what’s happening in games that kids are playing, like Roblox and Instagram and TikTok—and let’s not be fooled; Instagram and TikTok, they are games. This book really gives us some practical ways to ground ourselves and ground each other as it becomes harder and harder to separate fact from fiction, what’s real and what’s artificial.

Kornik: Yes. So interesting. You make some fascinating arguments in the book, one being that our collective future depends on the choices we make right now when it comes to all media, really, but essentially, Web3 and the metaverse and how that’s all going to play out, and how we communicate with each other through those mediums, right, through those new technologies. You suggest in the book that it's a crisis as serious as climate change but just not enough people are talking about it. Walk us through that a little bit if you could in terms of the burning platform that we have in front of us.

Casciotta: Well, yes. What’s really funny is, at least here in The States, it’s, whenever there’s a big commercial crisis, economic crisis of corporate magnitude, the same playbook comes out, right? The same thing happened with Big Tobacco. You see it with the concussion issue with the NFL and with tackle football. It’s like, “Let’s just wait until the data is conclusive.” That’s riddled with lots of issues in itself. When it comes to media technology… not everybody smokes, not everybody plays football, everybody lives in our current climate, and everybody uses media technology. This is the stuff that we utilize to literally communicate information and translate communication between entities, whether that’s individuals or entire governments to the masses. If we can’t get ahold of that reality—and I know regulation is a scary word in some circles, so I won’t say that, but if we’re not proactively giving this some forethought to put in some guardrails, some handholds, around the thing that we use to, again, to literally communicate every piece of information with each other, we should not be surprised when we have the issues that we’ve been retroactively dealing with, like the COVID crisis and the amount of misinformation/disinformation that has come out there when it comes to public health.

What I’m calling for is a little bit more forethought so that we’re not late to the game, whether we’re a business, whether we’re a government entity, and we’re not retroactively going, “Oh, my gosh. I wonder what happened. I wonder why this is such a big issue.” [Laughter] It’s a crisis and it needs to be thought of as one. There was actually a really brilliant paper that was done by a couple of folks. Really, it was a group of people across a ton of different disciplines that argued that media technology, social media, all of the stuff should be really elevated to the discipline of—to a crisis discipline, and I agree with that. I mentioned that in the book.

Kornik: Yes. Another one of the ideas that comes up in the book that I think is really interesting is this idea that you pointed out that in a metaverse future that we can flourish completely detached from our bodies essentially, right, our human form, and you think that’s pretty dangerous, that’s a dangerous mindset to get in, and I think that’s a pretty interesting concept. You say these shifts come at incredible psychological and societal costs. What are the answers? What can we do?

Casciotta: Well, I’d like to answer that question with a story. My family and I last year moved up to this little suburb outside of Columbus, Ohio called Westerville. I think, to many people, that looked like a very strange move. “What in the world is in Westerville, Ohio?” Well, for us it was really dear friends who felt like family, who were parenting their kids similarly to us in the way they saw social media and their use of media technology. For us it meant being near people that had similar values as we did, who knew us as our ordinary selves apart from any kind of personal brands we might be tempted to put out there. That to us was really, really important. What I found out, in the process of moving to Westerville, Ohio, is it actually used to be ground zero for the temperance movement. The whole headquarters was here. It was because they had a big printing factory and everything here and it was really interesting that this was like the place you wanted to go if you wanted to work for the temperance movement. The reality is that that movement eventually failed. It didn’t really work. It didn’t once they overregulated everything, and it’s like the data didn’t show that it stopped a lot of the issues it was trying to solve.

But then I did some more research in preparation for this book and I found out that just about an hour and a half away from us is the City of Akron, Ohio, and in the City of Akron, Ohio, something very interesting happened. You had two guys who were these struggling alcoholics who got together and decided that the very process of being in close proximity with each other actually helped their addiction, and they ended up starting Alcoholics Anonymous. My point in that story is that in this age, proximity matters.

Kornik: Well, you can certainly convince me that the pendulum has swung too far in one direction and that we needed a non-tech intervention, but I’m Gen X; I didn’t grow up with this technology all around me all the time. Isn’t there a real generational divide going on here? I mean, aren’t Gen Y and Gen Z wired differently, I mean almost literally?

Casciotta: They’re wired differently but what’s encouraging is that there’s a lot of data out there showing that Gen Z, and even Generation Alpha, are actually pushing back against a lot of the assumptions Big Tech has made over the past 20 years.

Kornik: Yes, and I’m curious, as those generations have entered the workforce or are entering the workforce and are starting to move up through the ranks and as they continue to become more senior leaders, what that impact, or what that could mean, for businesses, they start to begin to try to figure out how to balance technology and the humanity of running a company, the employees, the interaction between senior leaders and more junior level employees. What are the benefits of such a realization for business leaders as they start to look at the future through a different lens perhaps?

Casciotta: It’s a great question. I think it’s realizing that genuine human interaction, what I call ordinary human interaction, a break in the automation change, is in fact a competitive advantage. Customers don’t want to go through an automated phone process that gives them seven different prompts before they actually talk to a real person. In some ways, the antidote to just good enough is actually ordinary. To make that shift, it’s going to take a lot of education; obviously, education of the workforce, and then shareholders as well. I think realizing that human interaction ordinariness, that face-to-face, that flesh-to-flesh sort of conversation, is something that can actually give you a competitive edge, is the opportunity at stake.

The bigger question is are we, as employees, as human beings, in service to the technology or is the technology in service to us? Are we creating a future where we don’t really need people to work anymore? [Laughter] That’s fine, but then we need to drastically shift what society looks like from a governmental standpoint, from an economic standpoint, and we need to be asking those questions as business leaders now so that we’re not caught between…or with our tail between our legs in 10 to 15 years going, “Oh, my gosh. I didn’t see this happening. Now I have a revolution, a revolt, on our, on my hands.”

I think whatever outcome we decide on, a company decides on, whatever is best for their bottom line, that’s fine. Again, I’m not a Luddite, I’m not antitechnology, but I think we need to think a little bit more realistically, carefully, and take our time when it comes to recognizing both the intended and unintended consequences of innovating to the point of human beings not being necessary anymore to carry out some of the key functions they have been for over 100 years, if not more. <>Joe Kornik: Right. Which leads me right to my final question, which is where does this all end up? I mean when we do look out, let’s say, 10 or 15 years, how optimistic are you about the future in a world of humans and technology?

Casciotta: I’m an optimistic guy. I am pretty optimistic. I think it’s going to be like AA. It’s going to take enough ordinary people on a mass scale saying, “I don’t want this anymore. I don’t like this anymore. I don’t like feeling this way.”

Kornik: CJ, thank you so much for a fascinating discussion today.

Casciotta: Yes. Thank you for having me. Appreciate it.

Kornik: Thank you for watching the VISION by Protiviti interview. On behalf of CJ Casciotta, I’m Joe Kornik, we’ll see you next time.

Did you enjoy this content? For more like this, subscribe to the VISION by Protiviti newsletter.