Energy expert: A global ‘grand bargain’ will be required for complicated climate transition in India

IN BRIEF

- By 2030, India will be the most populous country on the planet and have the second largest economy behind only China. It’s critically important for us all that India gets its energy transition right.

- India has rapidly become one of the largest renewable energy markets globally with more than 100 GW of solar and wind assets contributing 36% of electricity capacity and 11% of output. By 2030, half of all energy is to come from renewable sources.

- India’s contribution to the greenhouse gases causing rising temperatures has been minimal: per capita, it emits a fraction of the GHGs of the United States, Europe or China.

A heatwave lingered across northern India for much of the pre-monsoon period from March and into June, bringing temperatures that approached 50°C (122°F) in some states and power outages for millions. The government responded to the energy shortfall by announcing an increase in coal generation and the re-opening of more than 100 mothballed mines.

The irony of responding to mounting evidence of climate change by actions which boost carbon emissions illustrates a core conundrum for India. On the one hand, India is among the countries most vulnerable to changes in the climate—including a risk to the monsoon pattern on which hundreds of millions of farmers rely, receding glaciers in the Himalayas which feed the great rivers of the north and east, and more intense storms and flooding.

Yet the politics of a noisy democracy make the hard decisions required for India’s sorely needed energy transition more difficult. The rising middle class aspire to the carbon-heavy lifestyles they see on streaming content—cars, travel and summer air conditioning. And politicians shy away from taking on the vested interests of King Coal, at least not while 77% of India’s power is generated in government-owned thermal plants and more than a million jobs in key states depend on the coal industry and its supply chain.

By 2030, India will be the most populous country on the planet and have the second largest economy behind only China. It’s critically important for us all that India gets this right.

At COP26 in Glasgow in November 2021, India’s climate dilemma was again on display. The Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, was an early advocate of climate action from his years as Chief Minister of Gujarat, and published a book entitled Convenient Action calling for radical policy change. He pleasantly surprised many by coming to Glasgow offering a more ambitious national contribution by 2030 and a net zero target date of 2070. In a fast-growing economy with a very low per-capita carbon footprint, these were genuinely stretching commitments. Yet it was India which, on the last scheduled day of the conference, held up the final Climate Pact by refusing to agree to the intent to “phase out” unabated coal usage, and instead settling for “phasing down” coal.

By 2030, India will be the most populous country on the planet and have the second largest economy behind only China. It’s critically important for us all that India gets this right.

From “King Coal” to renewables

In many ways, India’s policy response to the challenge of climate change has been impressive. Electricity generation is India’s lead source of carbon, representing some 35% of the country’s 3,200 MTCO2e (metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent) annual emissions. The country has rapidly become one of the largest renewable energy markets globally with more than 100 gigawatt (GW) of solar and wind assets contributing 36% of electricity capacity and 11% of output. The new target announced by Modi is for 500 GW of non-fossil generation by 2030, by which time half of all energy is to come from renewable sources.

India has focused particularly on solar generation. The National Solar Mission has succeeded in making solar the most cost-competitive and fastest growing power source. Falling capital costs and an intensely competitive market have resulted in solar generation at prices as low as 3 U.S. cents/kilowatt-hour (KwH), before the recent uptick in capital costs. Modi has led the creation of the International Solar Alliance and conceived the One Sun One World One Grid initiative designed to connect national grids to make solar a truly global resource.

Similarly ambitious has been India’s drive to decarbonise transportation, which accounts for some 10% of emissions. The target for blending of biofuels was raised to 20% by 2025. The government has announced the intent to electrify transportation by 2030 and is offering subsidies to the electric vehicle (EV) sector through the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles in India policy. In 2021, 329,000 electric vehicles were sold, up 169% from the year before. Most EVs so far are two- and three-wheelers for commercial use for intra-city passenger and goods movement.

Cohesive policy frameworks and increasingly compelling economics seem set to deliver material decarbonisation of electricity and road transportation in India over the coming decade. However, India’s energy transition towards carbon neutrality is far more challenged in harder-to-abate sectors such as agriculture (15% of emissions), buildings and construction (15%), and industry (11%), according to London’s Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

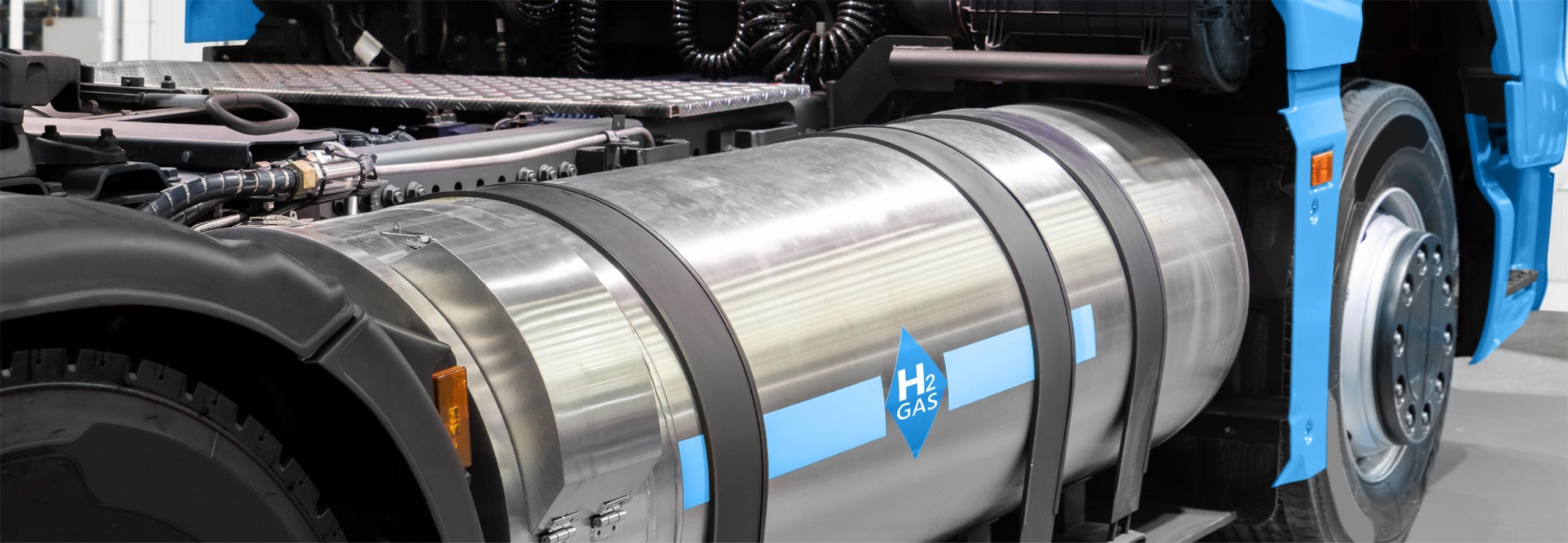

In February 2022, the government announced its green hydrogen policy, aiming to achieve 5 metric tons (MT) of output by 2030. While currently green hydrogen is an expensive option, plans have been announced to address the costs so energy-intensive industries such as steel, cement and aluminium can replace process coal and gas. In June 2022, Adani Group, India’s fastest-growing diversified business portfolio, and energy supermajor TotalEnergies of France partnered to create the world’s largest green hydrogen ecosystem, intending to invest $50 billion in green hydrogen in India.

169%↑

In 2021, 329,000 electric vehicles were sold, up 169% from the year before.

One alternative or complementary approach is large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS). India is thought to have the geological capacity to store 500 to 1,000 gigatons (GT) of carbon. However, this option is extremely costly and probably not viable, at least not any time soon.

A looming carbon tax

Given the economic realities, the only credible conclusion is that India’s energy transition beyond 2030 and journey to net carbon neutrality will require some form of carbon pricing. Scale manufacturing has driven down solar costs, and now seems set to do the same with batteries. But frontier technologies like green hydrogen and CCS are unlikely to be as attractive economically, even in the medium term, compared with their dirty and incumbent rivals. The slow pace of adoption of energy efficiency measures in homes, buildings and small businesses demonstrates the market lag that needs to be overcome in millions of distributed decisions across the vast country. Regulation and incentives are unlikely to force the pace of change needed without a robust price signalling that can only come from a carbon tax.

The Indian government, and indeed ordinary Indians, are justifiably irritated when they are lectured by foreigners about the steps India should take to control carbon emissions. India’s contribution to the greenhouse gases (GHGs) that are causing rising temperatures has been minimal. Per capita, it emits a fraction of the GHGs of the United States, Europe or China. Indians have every right to enjoy the economic growth that is now gathering pace and the benefits that derive from a more energy-intensive lifestyle. The actions of others seem set to have increasingly catastrophic impacts on ordinary Indians as temperatures increase, weather becomes more extreme, and sea levels rise.

Indians have every right to enjoy the economic growth that is now gathering pace and the benefits that derive from a more energy-intensive lifestyle.

At the same time, it is clearly true that it is in everyone’s interest, including that of India, that growth should become less carbon-intensive and more sustainable. The government of India has taken responsibility to change its power generation and transport sectors, but—as in other countries—needs to be careful about the politics of tackling coal and imposing new taxes.

The logical and ethical solution to India’s climate dilemma is a “grand bargain” with the global community, especially richer and more polluting nations. The government of India can turbo-charge India’s climate transition by pricing carbon across the economy in return for international partners offering climate finance at significant scale.

To achieve just India’s 2015 commitments at COP21 in Paris would require investment of $3 trillion, so estimates of the price tag for carbon neutrality are in excess of $20 trillion. Most of this debt and equity can come on commercial terms from private markets, given the underlying positive economics. The good news for international investors is that India’s climate transition offers a huge, long-term investment opportunity as India’s economy—currently the fastest growing in the world and rapidly moving from the fourth largest economy to the second by the end of the decade—commits to an epic and fundamental energy transformation.

It is in everyone’s interest, including that of India, that growth should become less carbon-intensive and more sustainable.