Protiviti’s Jonathan Wyatt: Personal transport will drive future cities’ success

IN BRIEF

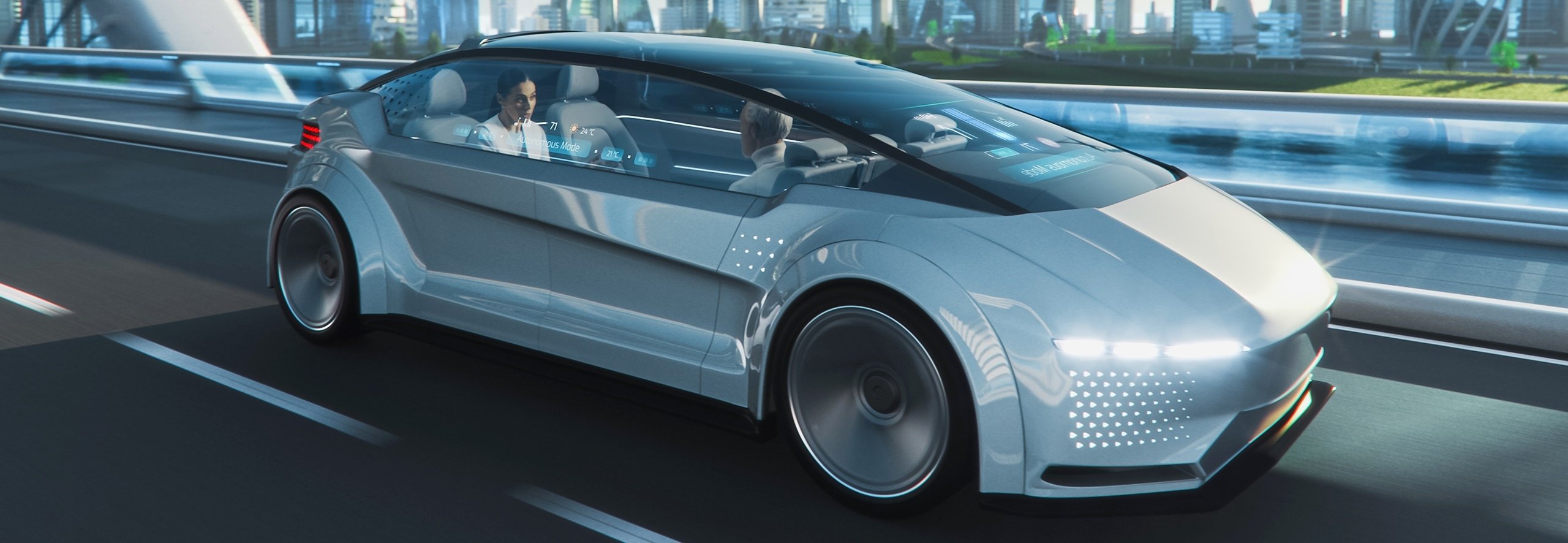

- Personal transport, not mass transit, is the way of the future.

- There will be fewer roads because they would be completely optimized to be efficient. There would be little to no traffic delays, and many existing roads could be re-imagined as green spaces.

- Amazon’s delivery routes, particularly in big cities, are completely optimized by computers. What they do with packages, we could do with people.

In this interview with Jonathan Wyatt, Europe Regional Market Leader for Protiviti, Joe Kornik, Editor-in-Chief of VISION by Protiviti, sits down with him to discuss mobility and how we’ll move around in cities in 2030 and beyond.

Kornik: As you think of cities in 2030, what are some of the big changes you see coming for the way we move around cities? What are the possibilities? What are some of the challenges?

Wyatt: Looking that far ahead is difficult. The real challenges are political, not technological. We have the technology today to completely change the way we look at transportation and provide a very high quality, personalized and efficient system. There are, however, many barriers to this. Some people like to own cars and will object if this right is taken away. Many people’s careers will be adversely impacted by automation and therefore the unions will resist change. We have already seen this with automation on trains. This requires leaders that are ready to take a stand to force the change through, and the right public mood to make it happen. COVID was one catalyst for change that forced us to take a leap. Climate change should be another.

Kornik: Leaders winning hearts and minds seems like a big ask, but particularly about something that requires a shift in thinking, like autonomous vehicles

Wyatt: Right. It’s also important to remember that one accident involving a driverless car could have a significant impact. The reality is, of course, that accidents with humans at the wheel happen all the time. Public reaction, however, can be very different when it is seen as a fault with the technology. Even though it is very irrational, there will be a tendency to over-act as a result of very occasional accidents, even if they occur with lesser frequency than they do now. The other key emotional issue is determining who is at fault in an accident and/or who to protect in situations whereby an accident is deemed inevitable. If a child steps out into a road unexpectedly and the vehicle cannot avoid an accident, do you protect the passenger or the child? Who makes this decision? Do you consider the demographics and/or medical history of the passenger when making these decisions? It’s these types of decisions that will delay adoption; not technological considerations.

Kornik: That makes sense, but I’m still stuck on whether people will willingly give up driving their own cars. Will they?

Wyatt: Like a lot of this, I think it’s generational. Look at the adoption rates of Uber and Lyft among younger people; it’s not even crossing their minds to own a car. This is the future. This is a rich topic for urban planners around the world. Beijing, China and Phoenix in the U.S. already have autonomous taxis. Whatever city decides to take that leap to eliminate personal cars completely would immediately become a leader on the world stage. It wouldn't surprise me if a city like London, where I’m based, made some bold decisions around transport, and maybe even banned petrol-driven cars sooner rather than later. A decision like this would set off a cascading chain of events that would, ultimately, result in a complete redesign of the city center—and ultimately, in my opinion, create a better city.

The real challenges are political, not technological. We have the technology today to completely change the way we look at transportation and provide a very high quality, personalized and efficient system.

Kornik: There will be first movers, for sure. Do you think most cities will be equipped to handle this potential new reality?

Wyatt: Car ownership, and especially electric vehicle ownership, is going to be a major issue for cities. People have to park those cars, and cities will have to put electric charging stations in public places all over the city. That’s an issue that cities are already dealing with, but if you don't want to have to solve that problem, you skip ahead to the point where you just ban personal cars in cities. An app will call an autonomous car to you, and it will take you where you want to go. You don’t have to park it, you don’t have to charge it, you don’t have to service it. All the technology already exists to do this, and the way forward seems obvious. Look at how Amazon delivers, particularly in big cities—the routes are completely optimized by computers. What they do with packages, we could do with people. For me, this should be the future: An autonomous vehicle picks you up and takes you exactly where you want to go in an efficient, convenient and environmentally responsible way.

Kornik: What about the massive infrastructure changes that would come along with this type of change?

Wyatt: There will be work required, of course, but it’ll lead to better cities. There should be little to no traffic delays because roads will be completely optimized, and the increased efficiency should result in fewer roads but probably the addition of what I’ll call superhighways, multilevel roadways that would accommodate many cars to keep other areas of the cities clear. Computers will manage the traffic flow so that there are no delays, no blockages and no accidents. Remember, in a world of fully autonomous vehicles, computers will manage the traffic flow so the vehicles can travel much faster than they do on current roads. Cars will constantly be communicating with other cars and adjusting speed accordingly. You can therefore have cars going through interchanges at high speeds in multiple directions. Scary to watch and no doubt slightly uncomfortable to experience initially, but completely safe, or at least significantly safer than the roads today. Many roads could be re-imagined as parks or green spaces or walking paths. This, of course, assumes that everybody can walk the last few hundred meters to their home. What about the elderly or people with a severe medical condition? What about deliveries of larger items? We’ll still need to find ways to get people and things right to their door. And we will; there will be alternative technological solutions to that problem.

Kornik: We haven’t touched on mass transit. What role does it play in cities of the future?

Wyatt: One of the big questions for cities, I think, is whether mass transit will still need to exist in cities of the future. Removing mass transit from city centers is probably going to happen; not by 2030, of course, but eventually. Today, I often see large, mostly empty buses and trains. We do that because we really don’t have an alternative, but we will soon. So, if mass transit is part of the long-term future, it will have to be radically redesigned for a completely new world. I certainly prefer the idea of personalized transit designed for the passengers, not the driver, with the capacity to enable a group travelling together to meet and socialize in comfort whilst travelling.

Kornik: It’s funny you say that because Los Angeles is part of a pilot program with the World Economic Forum to look at how to bring autonomous vehicles—flying taxis—to cities. Part of that plan is to make sure it is “mass transit” and not just for the super wealthy. What role do you see that playing in the future?

Wyatt: Whenever I see a city like that in a movie, it looks dreadful, and I certainly wouldn’t want to live there. To me, a pleasant city is one where it’s much easier to walk places or where you’ve got quiet electric vehicles that are personalized transport and optimized for full efficiency. I think the reason anyone is even considering flying vehicles—especially in a place like L.A.—is because it’s often too difficult to drive there so we need alternatives. So much of a city’s traffic is a consequence of the inefficiencies required to accommodate limitations of humans, as well as allowing for humans driving badly. It seems like flying taxis are going to be part of an urban future, but I’d rather look up and see sky, not traffic. I’m sure others feel differently, but for me the minute a city starts to feel chaotic, I start to look to a life in the country or by the sea. Now, I suppose if you happened to live right next to one of those superhighways I was talking about earlier, it could be horrific, I’ll admit. Still, probably no worse than living next to a seven-lane highway with lots of traffic today that runs through many cities. And it’ll be quieter. And cleaner. And some cities, I’m certain, with a little planning could find clever ways to hide those superhighways away.

Look at how Amazon delivers, particularly in big cities—the routes are completely optimized by computers. What they do with packages, we could do with people.