Protiviti-Oxford survey: Cities will be more strategically important in 2030

Protiviti-Oxford survey: Cities will be more strategically important in 2030

Protiviti-Oxford survey: Cities will be more strategically important in 2030

The city is back, and arguably never left, during the pandemic-induced hibernation and the lockdown of urban livelihoods and lifestyles. Cities are globally recognized as the engines of economic growth and the centers of social activity, and business leaders share a very positive view on the increasingly important role of cities for generating successful businesses. Cities will be increasingly more significant in 2030 as concentrated pools of labor, skills, new talent, and knowledge, according to key findings from the University of Oxford-Protiviti survey: Executive Outlook on Cities and Strategy, 2030.

City Size, Significance and Prestige

The desirability of particular cities over the next decade will increasingly be built on their essential attributes: 61% of global business leaders emphasize the growing benefits of city size, significance, and prestige. This viewpoint favoring larger, established cities is shared by 51% of North American respondents, 64% of European executives and 78% of business leaders in Asia-Pacific. Only 11% of business leaders in North America disagree with this point of view, followed by Europe (8%), and Asia-Pacific (6%). The overwhelming evidence suggests that global business leaders are backing big, influential “first-tier” cities as the prime sites for growing their enterprises.

First-tier, larger, and highly specialized urban economies will benefit most and will increase in importance for business operations. Second-tier, smaller cities, or those without adequate urban infrastructure, will find it difficult to compete to attract businesses. Meanwhile, having access to a large local customer base and a sizeable pool of talent will become increasingly important for businesses worldwide: 58% expect the benefits arising from the diversity of customers in a city to increase by 2030; 56% recognize the growing benefits of geographically concentrated labor pools and local talent.

Opportunities and Threats to Cities Worldwide

C-suite and corporate board members find cities attractive in very different ways. In North America and Asia-Pacific, the city as a technology hub is viewed as the dominant driver, with 46% of business leaders in North America and 48% in Asia-Pacific citing this as the major factor for an urban business (re)location. Access to a good educational system is the second most significant reason for North American business leaders, while tax incentives and a pro-business climate are of equal importance in Asia-Pacific for 40% of those surveyed. For 54% of European business leaders, with proportionately fewer major urban agglomerations and top research-intensive universities, the talent pool is seen as the main driver to attract business to a city, followed by good urban infrastructure.

DOWNLOAD your exclusive copy of the Oxford University & Protiviti Key Findings: Executive Outlook on Cities and Strategy, 2030.

At the same time, C-suite and board members across the world do not consider major threats to cities in the same way. In North America, 61% are most concerned about the political climate, regulation, and taxes, whilst 43% fret about the state of infrastructure. Surprisingly, with North America having just experienced its two hottest years on record in 2016 and 2020, punctuated by a series of extreme weather calamities, only 17% of the business leaders across the continent worry about the climate change impact on the natural and built environment.

In Europe, data privacy and cyber security (46%) and climate change and sustainability (46%) are the top two threats to urban life. In Asia-Pacific, in addition to cyber security (40%) and climate change (40%), the main worry is about the political climate and government regulation and taxes.

Conclusion

To sum up, business leaders recognize the potential global and local threats to cities and urban lifestyles, but the overall message remains that as cities thrive over the next decade, so will well-run urban-located businesses. The Oxford-Protiviti survey provided a sounding board for the views of global business leaders on the future of cities, and the importance of urban connectivity for their business operations over the next decade. The fundamentals of why cities work, how and why businesses are drawn to, compete, and flourish in cities, and what opportunities lie ahead for these urban centers have been considered across the world’s regions. The outlook for cities and the role of business in shaping our shared urban futures look positive.

Business leaders across the world have responded to say that despite earlier signs of a white-collar shift to move online, home-based work regimes, city locations matter, and will matter more by 2030. As C-suites consider post-pandemic markets and opportunities, the implications of this survey suggest that rejecting or reducing the urban roots of their businesses may have unintended consequences for commercial connectivity and competitiveness. The survey shows that the pandemic has consolidated the urban focus of business, rather than deflected attention away from big cities. Nevertheless, the survey indicated that in the midst of changing patterns of work and social interaction, business leaders are looking towards cities as their anchor for a successful, profitable future. While the fiscal implications and consequences are only now being considered by governments, business leaders are clearly seeing cities as the foundation of their recovery and growth pathways.

The survey signals that global C-suite and corporate board members share a positive outlook for cities in 2030, and express great confidence that cities will not just be the geographical midpoints of future economic growth, but the epicenters of social, cultural, and behavioral change over coming decades. By default, governments and policy-makers, urban practitioners and entrepreneurs will recognize their mutual interest in bringing back the bustle to cities, and building up the urban landscape once more for innovation, new business opportunities, and investment.

PROTIVITI-OXFORD SURVEY: CITIES WILL BE MORE STRATEGICALLY IMPORTANT IN 2030 - Video transcript

Joe Kornik: Welcome to the VISION by Protiviti interview. I’m Joe Kornik, Director of Brand Publishing and Editor-in-Chief of VISION by Protiviti. Our content initiative where we put megatrends under the microscope and looking into the future to examine the strategic implications of big topics that will impact the C-Suite and executive boardrooms worldwide. In this, our first topic, the Future of Cities, we’re exploring the evolution urban areas are undergoing and how those changes will alter cities over the next decade and beyond. As part of this initiative, Protiviti partnered with the University of Oxford’s Sustainable Urban Development Department to conduct a global survey of CEOs and executives to discover their perspectives on cities’ roles in their businesses in 2030 and beyond. Today, I’m joined by the team of Oxford professors who conducted the research, Dr. Vlad Mykhnenko, Dr. Nigel Mehdi, and Dr. David Howard. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Vlad Mykhnenko: Thank you. I’m really happy to be here.

Joe Kornik: When we think about what makes a city successful, there’s a whole host of things we think about that sort of influence that but it’s typically not how CEOs view cities. This is a pretty unique survey in that it’s asking for global executives’ perspectives on cities in 2030 and specifically how they view their future as part of their overall business strategy. Why is that so important in the future success of cities around the world?

Vlad Mykhnenko: I think one way of understanding cities is to look at them as special concentrations of firms, people, and organizations. So, firms are really important because they drive growth. They just offer dozens of different benefits to firms as firms drive growth. So, the decisions of firms where to locate and where to relocate are really vital and I think the local authorities and local stakeholders must really understand the perspective of business in cities to try to influence their decision.

Joe Kornik: What was the biggest takeaway from the survey? How do cities factor into the future for CEOs?

Vlad Mykhnenko: I think undoubtedly, the biggest takeaway has been defining that a huge majority of global business leaders. Sixty-four percent of global business leaders believe that the role of cities for their business will increase in the next 10 years and only 6% are tiny minorities. Only 6% believe that the royalties will decrease. I think that is a really, really important finding.<>Joe Kornik: Wow. That’s rather a ringing endorsement for cities, isn’t it? Some of those figures particularly that only 6% of leaders believe the role of cities will become less important for their business by 2030, especially when we consider which cities have been of late including a global pandemic, is rather stunning. So, I’ll open this up to all of you. What were some of the other surprising takeaways from the survey?

David Howard: Well, I think the pandemic has really consolidated the leaders’ reliance in some ways on larger incentives and particularly important having access to a talent pool of skilled labor, pools of having access to urban infrastructure and digital infrastructure. I think one of the most interesting takebacks really or takeaways from the survey was that 61% of business leaders in North America had said that they thought that the cost of urban location would decline or stay the same over the next 10 years. That’s a significant advantage of locating in a city. In Asia Pacific and Europe, the percentage of business leaders were 50% and 42% in terms of recognizing the cost benefit of remaining or moving to a larger urban center.

Nigel Mehdi: I think one big surprise was that CEOs are expecting the state of public infrastructure in their cities to improve by 2030. Leaders in all regions indicated expected improvements in public infrastructure; 75% in North America, 80% in Europe, and 82% in Asia Pacific.

Joe Kornik: So, as we come out of the pandemic, it seems the temptation for executives and corporations to sort of pull out of cities is there, right? I mean, save on some of those real estate costs that your workers continue to work remotely. So far, it’s been a fairly successful experiment, I think the remote work, at least in professional services. A lot of companies have done just fine during the pandemic but this data suggests otherwise, doesn’t it and why is that?

Nigel Mehdi: Yes, I think the gauge across all questions in the survey suggests confidence in the increasing role of cities over the next 10 years. Fifty-six percent of business leaders recognized the benefits of a geographically concentrated labor pool and I think that suggests that the role of cities is not going to decline regardless of the early indications of changes in occupation patterns as a result of the pandemic.

Joe Kornik: Yes, very interesting. I know the findings indicate that there’ll be a real distinction between first-tier or highly specialized cities which tend to be larger versus what are often referred to as second-tier cities which tend to be smaller. What conclusions did this survey reveal about those distinctions and each of those types of cities places in the future?

Vlad Mykhnenko: Well, absolutely right. We know that the share and importance of larger cities has been increasing. Today, about 33% of population lives in cities which are 300,000 inhabitants and above. So, larger cities have been increasing their importance generally and so it’s not surprising for us to find the finding that 61% of global business leaders believe that the benefits arising to their firms from the city size, from significance of cities from prestige will increase. What I think is important for the stakeholders in what you refer second-tier cities, perhaps smaller cities, perhaps less specialized cities are that the survey also offers a number of business fundamentals that can be improved in their cities: business environment, educational base, physical infrastructure, and politics. Those things, those levers can be tweaked to improve the significance of the cities for the business. I think those are very important also findings for the second-tier cities and their businesses.

Joe Kornik: One of the aspects of this survey I find really interesting, was the difference of opinion among CEOs in North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific, some of the regions that the survey touched. What were some of the more eye-opening takeaways from a geographical perspective?

Nigel Mehdi: Well, global business leaders find North American, European, and Asia Pacific cities attractive in very different ways. In North America, access to effective technology and good education was seen as a key. In Europe, the availability of talented labor pool and good public infrastructure are the leading attractions. While in Asia Pacific, access to the state-of-the-art technology is a requirement, but so are tax incentives and pro-business deregulation.

Joe Kornik: Finally, you asked executives about what could attract their business to a city and the other side of the coin, what they view is perhaps the biggest threat to cities over the next decade. So, what did they have to say about that in the research?

David Howard: Well, I think in terms of the attractions as a real emphasis on having access to good technology and educational, education skills services to provide that talented and skilled labor force. I think in terms of the threats, one that really stood out for me and for my colleagues is that in North America, 61% of business leaders believe that the critical context was going to be a potential threat particularly in terms of taxation and business regulation schemes and regimes in North America. In Asia Pacific and Europe, there was a 42% of concern, if you will, of leaders who were thinking about the possible disadvantages that the political context of their location is going to offer. Also, in Europe and Asia Pacific, I think it’s also interesting that over 40% of business leaders were concerned about climate change and a similar figure around 40%, or mid 40% of business leaders in those two regions, in Europe and Asia Pacific, were concerned about cybersecurity, cybercrime, and data privacy issues. Whereas conversely, in the US, only 70% of North American business leaders were concerned about climate change and data privacy which is similarly not important amongst North American business leaders.

Joe Kornik: Yes, really interesting. Thank you again, Vlad, Nigel, and David, for this really unique look inside this really detailed survey about CEOs and their perceptions of cities and their business strategy in 2030 and beyond. We appreciate the snapshot. Thanks again for being on the program and we’ll see you next time.. [Music]<>Back to video

DOWNLOAD your exclusive copy of the Oxford University & Protiviti Key Findings: Executive Outlook on Cities and Strategy, 2030.

The survey signals that global C-suite and corporate board members share a positive outlook for cities in 2030, and express great confidence that cities will not just be the geographical midpoints of future economic growth, but the epicenters of social, cultural, and behavioral change over coming decades.

Dr. Nigel Mehdi is Course Director in Sustainable Urban Development, University of Oxford. An urban economist by background, Mehdi is a chartered surveyor working at the intersection of information technology, the built environment and urban sustainability. Nigel gained his PhD in Real Estate Economics from the London School of Economics and he holds postgraduate qualifications in Politics, Development and Democratic Education, Digital Education and Software Engineering. He is a Fellow at Kellogg College.

Dr. David Howard, Director of Studies, Sustainable Urban Development Program, University of Oxford and a Fellow of Kellogg College, Oxford. He is Director for the DPhil in Sustainable Urban Development and Director of Studies for the Sustainable Urban Development Program at the University of Oxford, which promotes lifelong learning for those with professional and personal interests in urban development. David is also Co-Director of the Global Centre on Healthcare and Urbanization at Kellogg College, which hosts public debates and promotes research on key urban issues.

Dr. Vlad Mykhnenko is an Associate Professor, Sustainable Urban Development, University of Oxford. He is an economic geographer, whose research agenda revolves around one key question: “What can economic geography contribute to our understanding of this or that problem?” Substantively, Mykhnenko’s academic research is devoted to geographical political economy – a trans-disciplinary study of the variegated landscape of capitalism. Since 2003, he has produced well over 100 research outputs, including books, journal articles, other documents, and digital artefacts.

Protiviti's Claire Gotham and Tyler Chase on powering the city of the future

Protiviti's Claire Gotham and Tyler Chase on powering the city of the future

Protiviti's Claire Gotham and Tyler Chase on powering the city of the future

Amanda, a thirty-something professional, is a typical urban dweller in the year 2030. She wakes up each morning in a city apartment that is served mostly by electricity—but the sources of that power are quite varied. A heat pump from the coffee roastery in the building next door provides much of the space heating for her apartment. A photovoltaic cell on her balcony supplies the power for her coffee maker and other small appliances. Her tiny apartment and electric vehicle (EV), which has been charging overnight in the underground parking garage, both receive much of their energy from the local utility. The utility, in turn, generates its electricity largely from renewables such as wind power and solar panels.

Amanda is not just an energy consumer. She is also an energy provider through her building’s microgrid, which sells excess electricity back to the utility. The microgrid, which serves both residents and a data center business on the ground floor of Amanda’s building, is composed of EVs, photovoltaic cells, rooftop solar panels, and behind-the-meter batteries and generators used for emergency backup—a closed-loop system that provides minute-by-minute transparency via a building power dashboard and can be controlled by the users.

Unlike power consumers of today, Amanda enjoys energy supplied by a grid that is largely self-sufficient, resilient and green. If the local utility should suffer from equipment outages or overloads, her microgrid and those of neighboring buildings can pick up much of the slack. Moreover, her carbon footprint is a fraction of the typical consumer of 2021. Living in a compact city where multiple-use zoning is the rule, she can find practically every lifestyle need within a 15-minute ride.

If this scenario sounds too idealized, bear in mind that most of the technology to achieve it already exists. The real question is whether 21st-century cities will embrace the policy and business decisions that will turn sustainable energy into a reality.

Economic, climate and societal pressure is building to push for this future. Based on a number of indicators, such as the rapid growth of cities, which currently consume 78% of the planet’s primary energy, electricity use is going to soar in the coming years. Burgeoning technologies like EVs and distributed ledger systems (e.g., cryptocurrency) will need massive amounts of power, as will all the data centers that form the backbone of the digital economy. And legacy technologies, such as air conditioners, are not going to disappear overnight, which means the hunger for energy—and for renewable sources of that energy—will grow for the foreseeable future. For example, the International Energy Agency has forecast that the number of installed air conditioners will grow by two-thirds from the 2 billion units currently installed.

Climate change is a pressing point. As the planet warms, not only is the need for cooling technologies growing, but extreme weather events are causing widespread disruptions in electricity supply. Electric grids with built-in resilience are becoming a necessity, and yet the current model of centralized, often-remote energy generation and long-distance transmission is not set up to meet that need. A new generation of power companies is capitalizing on this weakness of traditional utilities by grabbing large sections of the power market, such as airports, hospitals and school districts, which depend on reliable energy, and supplying them with efficient, reliable, locally generated and locally stored energy—typically from clean and renewable sources such as wind and solar. These disruptors are growing in number and market share, with a projected market value compound annual growth rate of 27% for the next six years.

And then there is the customer, who with each passing year is having a greater influence on the future of energy. Whether through Wall Street, Main Street or government, the investing, buying and voting public wants to know the source of its electricity. A number of cities, such as San Francisco, already offer utility customers green energy options. And much like the organic food movement of the last century, consumers are indicating that they will pay more for personal and community health.

Climate change is a pressing point. As the planet warms, not only is the need for cooling technologies growing, but extreme weather events are causing widespread disruptions in electricity supply.

Future-enabling energy policies

While stakeholders ranging from government and business leaders to consumers and community activists appear as the face of the sustainable energy movement, economic forces in and of themselves are driving 21st-century economies toward renewable energy and electrification. The banking firm Goldman Sachs has forecast that investment in the clean energy sector will hit $16 trillion through 2030, surpassing fossil fuels. In line with those figures, Rewiring America, a nonprofit organization devoted to complete electrification of the country, has predicted the creation of 25 million new jobs of all types in the United States over the next 15 years, with five million sustained jobs by mid-century.

Government leaders are facilitating the transition toward renewables through such measures as stricter vehicle emission standards, phase-out programs for internal combustion engine vehicles, and subsidized campaigns to build widespread access to EV charging stations. The United Kingdom, for its part, has created Clean Air Zones (CAZs) on its roads and in its cities where polluting vehicles must pay a toll.

Partnerships between utilities and governments at all levels further promote electrification of final energy use. For example, a number of investor- and government-funded grid modernization projects are underway in the United States to make grids more responsive to changes in demand and supply, and to connect with and optimize input from microgrids. Currently, obtaining regulatory approval for such utility expenditures takes an average of 13 months.

Much wider partnerships involving government and businesses of all kinds could dramatically improve energy efficiency through the development of compact cities. With better land use, consolidated urban housing, and multiple-use buildings, cities can produce fewer emissions, require far less energy and promote healthier and happier lifestyles. Stockholm and Pittsburgh, for example, have comparable populations, but Pittsburgh sprawls over five times more land than Stockholm and produces five times the amount of emissions per resident. By contrast, Stockholm’s compactness enables it to produce a flourishing economy and a well-regarded quality of life.

These growing trends only touch the surface of policy shifts that could greatly enhance the energy efficiency of cities. Other changes include a circular economy approach that considers the energy use of all civic and infrastructure components, such as water, waste and building materials in comprehensive, interconnected ways, as well as cross-industrial synergies, such as those created by automakers and utilities working together to develop EVs and EV infrastructure.

The banking firm Goldman Sachs has forecast that investment in the clean energy sector will hit $16 trillion through 2030, surpassing fossil fuels.

Claire Gotham is a Managing Director at Protiviti and the Lead for Power & Utilities in North America. In her 25 years in the energy industry she has worked with senior leadership, to innovate on a wide range solutions across all segments of the industry, including risk, resiliency & sustainability.

Tyler serves as the global leader for Protiviti’s Energy & Utilities industry and has spent over 20 years focused on the wide ranging challenges in the industry. Tyler teams with a global network of experts across the Power & Utilities, Renewables, Oil & Gas, and Mining segments to stay ahead of trends and build solutions that enable success across the industry.

Did you enjoy this content? For more like this, subscribe to the VISION by Protiviti newsletter.

Veda Praxis: Eying Indonesia’s capital move out of Jakarta through a digital lens

Veda Praxis: Eying Indonesia’s capital move out of Jakarta through a digital lens

Veda Praxis: Eying Indonesia’s capital move out of Jakarta through a digital lens

The relocation of the Indonesian capital has been on the central government’s agenda for a long time and has yet to be realized. The proposal to move the capital to Palangkaraya or Samarinda, Kalimantan was first put forward some 60 years ago and has been revisited several times since. The latest, and most definitive attempt came in August 2021, when President Joko Widodo announced the location for the new capital city—an area that stretches across North Penajem Paser Regency and Kutai Kertanegara Regency, East Kalimantan. The potential cost of the move, along with the massive disruption to daily life, merit further examination of the challenges and opportunities to be faced in the development of the new capital. This article attempts to offer an increasingly important techno-governance lens on the relocation proposal from Veda Praxis, a governance improvement innovation firm based in Jakarta. Some key takeaways are provided to help the Indonesian government prepare for a better and more forward-looking digital presence. Why a new capital? There are several motivating factors that have been commonly touted to drive the urge for a new capital. We have highlighted three.

-

Superdensity challenge. Both Jakarta and the island of Java, where the current capital is located, are facing the issue of rapid and uncontrolled population growth. At more than 270 million people, Indonesia's population remains concentrated on the island of Java with more than 151 million people or about 52% of the national population. The central role that Jakarta plays is highlighted by the fact that the vibrant city is viewed as the center of both Indonesia’s government and business. This has led to the superdensity of the current capital. With an area spanning some 622.33 km2 and a population of over 11 million (16,704 people/km2), the capital’s density far exceeds any other area in Indonesia. Euromonitor International predicts that Jakarta will replace Tokyo as the most populous city in the world by 2030. Severe congestion and other mobility issues could cripple the city. A 2020 congestion survey names Jakarta as one of the worst congested regions in the world, ranking it 10th with an average congestion of 53% and a peak congestion of 87% during working hours.

-

Wealth distribution. Despite the emergence of new urban centers and campaigns for infrastructure distribution to other islands, the wealth of Indonesia remains in Jakarta (Even the growing infrastructure projects that have been sprouting in other regions have not matched the output of the country’s most populous island. The population concentration is followed by the unequal distribution of Indonesia’s gross domestic product (GDP). Java’s economic output accounts for about 59% of the country’s GDP in the period from January to March. Amid the population inequality, there is a significant gap between the GPD contributions of each island. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics shows that Java still contributed a majority of the country’s GDP in 2020, accounting for 59% of the total national GDP. The issue of inequality remains unsolved. The government’s plan to establish a new location in an area at the center of Indonesia is an effort to fix the imbalance by creating a need for governance, investment, business, mobility, and wealth in a new capital of Indonesia.

-

Environmental imbalance. Various environmental issues have been plaguing both Jakarta and the island of Java. Java is facing the worst water crisis ever seen in Indonesia. The greater Jakarta area is facing extreme water scarcity, which does not occur in the surrounding areas. Furthermore, land subsidence has been occurring at the rate of 10-20 cm per year, making the coastal city vulnerable to sinking below sea level. Another concern is that land conversion or consumption on the island of Java is occurring five times faster than in Kalimantan. It is predicted that by 2030, overdevelopment in Java could reach 43%, threatening local heritage.

At more than 270 million people, Indonesia's population remains concentrated on the island of Java with more than 151 million people or about 52% of the national population.

The new capital

The new state capital will be located in East Kalimantan, in an area that stretches across the two regencies of North Penajam Paser and Kutai Kartanegara. Many factors were taken into consideration in determining the location for the new capital. Socio-economic disparity and population density in Java are the main factors that led to the decision to move the capital city to East Kalimantan. The state capital-to-be will span an area of 256,142 hectares (about 989 square miles), consisting of 5,664 hectares (about 22 square miles) for the planned central government core and 56,180 hectares (about 217 square miles) for the planned state capital area. The remaining area is earmarked for the expansion of the state capital.

The Indonesian government has made various preparations for the move, including finding the proper location, establishing a budget of IDR573 trillion (about US$40 billion) under three financing plans, and setting up a special governance for the region. The development of the new capital will also be focused on the environment and digitalization, adopting green government by enforcing green space and fully environmentally friendly construction. In terms of digitalization, the plan has carefully accounted for future infrastructure needs to enable digital transformation and a smart city design geared toward information and communication technology (ICT) to support connectivity and enhanced logistics.

Considering the development of the region as part of the state capital, population in the new capital city is expected to surge through 2045. The total number of residents in the region is expected to gradually increase from about 100,000 residents to between 600,000 and 700,000 residents in 2025, 1.5 to 1.6 million residents in 2035, and 1.7 to 1.9 million residents in 2045, according to Indonesia’s Ministry of National Development Planning.

Strategic digital view

Indonesia is greatly diverse in many aspects—socio-cultural, geographic, local government profiles, and economic potential—which certainly poses a unique level of complexity. Such diversity, however, has also generated a lateral potential value that could serve as a global competitive advantage. Spanning an area of 1.9 million km2, Indonesia needs to go digital if it wants to gain a sustainable competitive advantage. The new capital may further push digitalization within the Indonesian government as the primary enabler of a new, digital economy. Digital infrastructure, business processes and services must therefore be carefully crafted to equip the new capital with digital innovation capabilities. The following six strategic technological considerations help analyze a range of high-level matters in the context of techno-governance.

Strategic planning

Digitalization and the green government concept will likely be the major drivers in the government’s effort towards its smart, green, beautiful, and sustainable vision for the new capital. The need to adopt smart interconnected technologies has been repeatedly highlighted by President Widodo when talking about plans for the new capital.

Digital governance

With respect to the new capital city, digital governance focuses on establishing stewardship, accountability, roles, and decision-making authority for the city’s digital presence. The Indonesian government needs to establish a well-designed digital governance framework to prevent misalignment during the execution of the digital strategy. The governance framework specifies who determines the direction for the new capital’s digital presence; a range of rules associated with the government-citizen digital activity; and the decision authority on digital investments.

Considering the extent of the digital vision for the new capital, and the fact that such governance will be deployed in a brand-new environment, vastly different challenges emerge compared to deployment in a relatively mature and stable environment like Java. Prioritizing compliance and risk mitigation in such an unpredictable environment at the early stages of the digital state capital might prove to be ineffective. The government needs to provide a flexible digital governance program that accommodates multiple initiatives without sacrificing structure and accountability.

From a smart city to a smart nation

More than the physical relocation of governmental buildings, the anticipated capital move provides opportunity for the rise of Indonesia as a digital nation. Therefore, the preparation needs to cover the management of not only a smart city, but a smart nation. Indonesia has begun a smart city transformation in a number of big cities in the country, even joining the ASEAC Smart Cities Network (ASCN) in 2018, which fosters the sharing of good practices and knowledge.

The smart city concept is key for driving innovation and preventing and overcoming various problems, and, ultimately, improving the quality of life for the country’s residents through the use of ICT. However, strong infrastructure, technological ecosystem and networks are needed for a functioning smart city. Extreme transformation in terms of digital mindset, regulation and infrastructure is extremely important considering that Indonesia is ranked 40th out of 64 countries globally in the Digital Government Ranking report by Waseda University, Indonesia.

Building an adequate technological ecosystem to support the smart properties of the capital is one of the challenges faced by the government. Technological infrastructure such as CCTV, traffic lights, optimized digital population data, as well as weather monitoring technology—including rainfall, wind, and Air Quality Index (AQI) is needed. A strong backbone network is required to connect the thousands of technological devices of different types that will be spread across the capital city. Additionally, connecting various devices means that a large amount of data will be generated every second. It will be a unique challenge to ensure that such data is easily accessible and adequately scalable to support the decision-making process in improving the quality of services as well as government operations.

The road to a smart nation begins with the establishment of the capital city as a digitally enabled society hub. Here, the mobile-first concept can be used as the foundation for all public services. This requires a combination of data-driven services and smart collaboration based on the data obtained from the OpenAPI and microservice architecture used in a wide array of constantly interconnected digital objects. Such digital experience will in turn improve the digital literacy of residents through the experience of utilizing available Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, Exhibitions (MICE) buildings. To build these capabilities requires optimizing a range of infrastructure technologies such as hyperscale cloud service, integrated smart waste sensors, 5G connectivity, and fiber optic support.

The following principles will provide room for a balanced governance program:

-

Support the advancement of initiatives at the individual or unit level while maintaining an inventory of information on those initiatives.

-

Implement decentralized governance as the units grow more mature digitally.

-

Challenge the governmental units to come up with ideation but centralize evaluation and prioritization.

-

Establish a proper responsibility accounting system with properly mapped KPIs for the digital initiative.

-

Develop the governmental digital solution around the business process to ensure data compatibility, technical consistency and agile integration.

E-Government

Despite the dream of becoming a digitally enabled nation, government services have been plagued by unintegrated data, siloed data, lack of information sharing and ownership, and unpredictable business processes. This has resulted in dissatisfactions and poor system performance. Presidential Regulation (PP) No. 95/2018 marked growing expectation for a better integrated electronic-based government system (SPBE). It provides a regulatory framework for national digital transformation covering four major domains: internal policy, governance, management, and service. The launch of SPBE aims to create efficient, effective, transparent, and accountable work processes and improve the quality of public services.

SPBE measures the maturity level of 47 e-Government indicators as the subcomponents of the four domains. These indicators include data center infrastructure, open data, business process innovation, government sharing system, infrastructure audit, application and security, risk management, change management, intra-government network, data management practices, appointed task force for SPBE, and central-local government integration. SPBE infrastructure development must be accelerated within a period of three years, including the development of an intra-government network.

The capital city establishment might both be influenced by and influence future e-Government regulations. In its strategic plan, the Ministry of Communication and Information has targeted for the 100% completion of the national data center. The national data center will be constructed in two locations—Jakarta and the new capital city. Meanwhile, the Indonesian One Data policy as mandated by Presidential Regulation No. 39/2019 is expected to heavily influence the design of big data architecture and infrastructure for the future capital city. Lastly, the SPBE regulation requires all governmental units to use the National API Gateway in delivering their services. To what extent the API Gateway will influence the architecture of information and services of the new capital needs to be considered in determining the direction of the strategic planning and governance.

Digital talent

The establishment of a smart city is necessary to accommodate the future needs of Indonesia’s young digital talent. Between 2030 and 2040, Indonesian professionals in the 15 to 64 age group will make up 64% of the total population. The jobs available will be more automated, digitalized, and dynamic. As the relocation deadline is fast approaching, the Indonesian government should start preparing the workforce for the coming digital innovations of the new capital city. Digital talent demands in the future will shift towards generalists that demonstrate cognitive, interpersonal, and self-leadership skill sets supported by specialized digital proficiency. The new capital strategy should take digital talent acquisition into account as it will determine the target set for the level of digital maturity of the working and living experience.

Security

In the development of a smart city, the most important infrastructure other than cloud or cloud computing for data storage and maintenance is the network. Problems such as hacking, submarine cable disruption, and other issues can break the main or backbone network. Without a backbone network, devices and platforms cannot communicate with each other, cutting access to the monitoring system and applications and thus interfering in decision-making as well as with public and government services.

Business continuity practices are pivotal to ensure uninterrupted connectivity at the state capital to prevent down time. For a continuous network, a backup system and extensive network consisting of different networks and backup data centers are vital to ensure the continuity of the technological services.

In addition to maintaining continuous network availability, a smart city must protect the privacy of residents against cyber threats. The long and complex process of the drafting of the Privacy Data Protection Act has threatened the privacy of the population. Cases of population data leakage are frequently found, in which population data is processed and stored without any protection and encryption.

64%↑

Between 2030 and 2040, Indonesian professionals in the 15 to 64 age group will make up 64% of the total population.

Hamzah Ritchi is Veda Praxis' research partner and both an associate professor and Head of Center for Digital Innovation Studies at University of Padjadjaran, Indonesia. Ritchi is an expert in business process management and innovation, accounting information systems, and IS governance with more than 15 years’ experience in consulting services and research. Ritchi has a keen interest in process science and analytics, the cognitive aspect of information systems, risk and internal controls, and IS governance.

Syahraki Syahrir is Veda Praxis' Chief Advisory and President of the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA), Indonesia Chapter. He holds several GRC-related certifications, including CISA (Certified Information System Auditor), CISM (Certified Information Security Manager), CDPSE (Certified Data Privacy Solutions Engineer), and GRCP/GRCA (Governance Risk and Compliance Professional and Auditor). He holds a degree in accounting from Padjajaran University and Master of Management degree from Binus Business School Indonesia.

Protiviti’s Jonathan Wyatt: Personal transport will drive future cities’ success

Protiviti’s Jonathan Wyatt: Personal transport will drive future cities’ success

Protiviti’s Jonathan Wyatt: Personal transport will drive future cities’ success

In this interview with Jonathan Wyatt, Europe Regional Market Leader for Protiviti, Joe Kornik, Editor-in-Chief of VISION by Protiviti, sits down with him to discuss mobility and how we’ll move around in cities in 2030 and beyond.

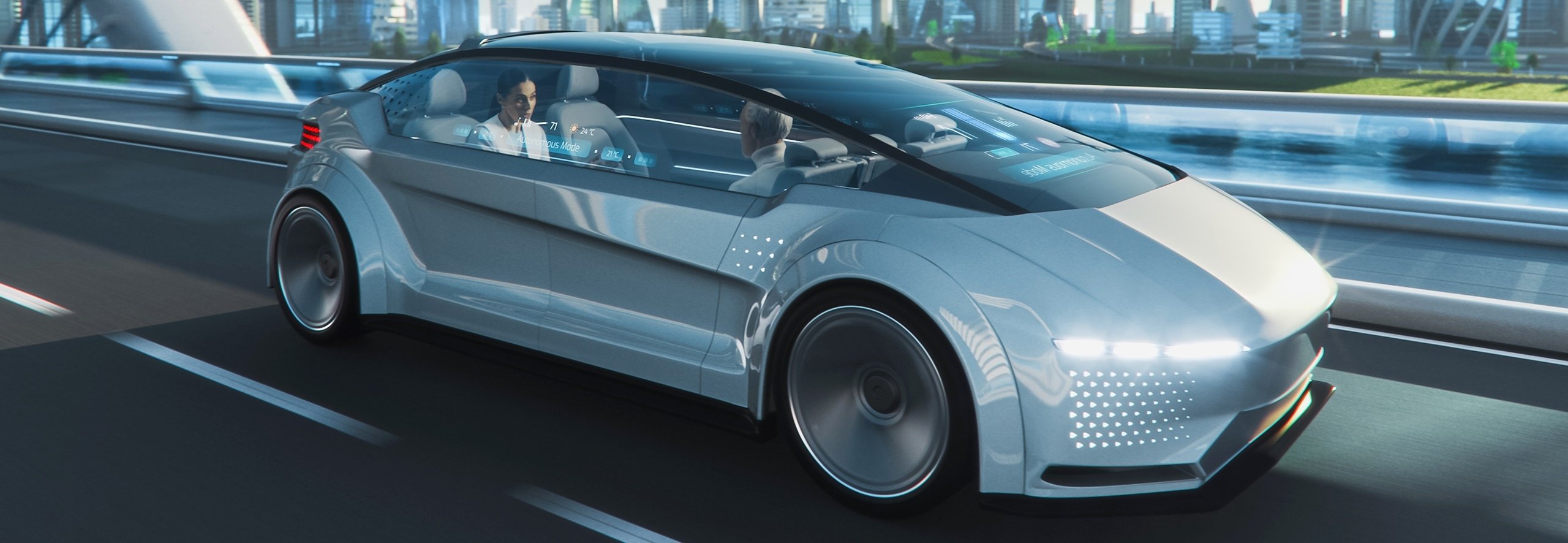

Kornik: As you think of cities in 2030, what are some of the big changes you see coming for the way we move around cities? What are the possibilities? What are some of the challenges?

Wyatt: Looking that far ahead is difficult. The real challenges are political, not technological. We have the technology today to completely change the way we look at transportation and provide a very high quality, personalized and efficient system. There are, however, many barriers to this. Some people like to own cars and will object if this right is taken away. Many people’s careers will be adversely impacted by automation and therefore the unions will resist change. We have already seen this with automation on trains. This requires leaders that are ready to take a stand to force the change through, and the right public mood to make it happen. COVID was one catalyst for change that forced us to take a leap. Climate change should be another.

Kornik: Leaders winning hearts and minds seems like a big ask, but particularly about something that requires a shift in thinking, like autonomous vehicles

Wyatt: Right. It’s also important to remember that one accident involving a driverless car could have a significant impact. The reality is, of course, that accidents with humans at the wheel happen all the time. Public reaction, however, can be very different when it is seen as a fault with the technology. Even though it is very irrational, there will be a tendency to over-act as a result of very occasional accidents, even if they occur with lesser frequency than they do now. The other key emotional issue is determining who is at fault in an accident and/or who to protect in situations whereby an accident is deemed inevitable. If a child steps out into a road unexpectedly and the vehicle cannot avoid an accident, do you protect the passenger or the child? Who makes this decision? Do you consider the demographics and/or medical history of the passenger when making these decisions? It’s these types of decisions that will delay adoption; not technological considerations.

Kornik: That makes sense, but I’m still stuck on whether people will willingly give up driving their own cars. Will they?

Wyatt: Like a lot of this, I think it’s generational. Look at the adoption rates of Uber and Lyft among younger people; it’s not even crossing their minds to own a car. This is the future. This is a rich topic for urban planners around the world. Beijing, China and Phoenix in the U.S. already have autonomous taxis. Whatever city decides to take that leap to eliminate personal cars completely would immediately become a leader on the world stage. It wouldn't surprise me if a city like London, where I’m based, made some bold decisions around transport, and maybe even banned petrol-driven cars sooner rather than later. A decision like this would set off a cascading chain of events that would, ultimately, result in a complete redesign of the city center—and ultimately, in my opinion, create a better city.

The real challenges are political, not technological. We have the technology today to completely change the way we look at transportation and provide a very high quality, personalized and efficient system.

Kornik: There will be first movers, for sure. Do you think most cities will be equipped to handle this potential new reality?

Wyatt: Car ownership, and especially electric vehicle ownership, is going to be a major issue for cities. People have to park those cars, and cities will have to put electric charging stations in public places all over the city. That’s an issue that cities are already dealing with, but if you don't want to have to solve that problem, you skip ahead to the point where you just ban personal cars in cities. An app will call an autonomous car to you, and it will take you where you want to go. You don’t have to park it, you don’t have to charge it, you don’t have to service it. All the technology already exists to do this, and the way forward seems obvious. Look at how Amazon delivers, particularly in big cities—the routes are completely optimized by computers. What they do with packages, we could do with people. For me, this should be the future: An autonomous vehicle picks you up and takes you exactly where you want to go in an efficient, convenient and environmentally responsible way.

Kornik: What about the massive infrastructure changes that would come along with this type of change?

Wyatt: There will be work required, of course, but it’ll lead to better cities. There should be little to no traffic delays because roads will be completely optimized, and the increased efficiency should result in fewer roads but probably the addition of what I’ll call superhighways, multilevel roadways that would accommodate many cars to keep other areas of the cities clear. Computers will manage the traffic flow so that there are no delays, no blockages and no accidents. Remember, in a world of fully autonomous vehicles, computers will manage the traffic flow so the vehicles can travel much faster than they do on current roads. Cars will constantly be communicating with other cars and adjusting speed accordingly. You can therefore have cars going through interchanges at high speeds in multiple directions. Scary to watch and no doubt slightly uncomfortable to experience initially, but completely safe, or at least significantly safer than the roads today. Many roads could be re-imagined as parks or green spaces or walking paths. This, of course, assumes that everybody can walk the last few hundred meters to their home. What about the elderly or people with a severe medical condition? What about deliveries of larger items? We’ll still need to find ways to get people and things right to their door. And we will; there will be alternative technological solutions to that problem.

Kornik: We haven’t touched on mass transit. What role does it play in cities of the future?

Wyatt: One of the big questions for cities, I think, is whether mass transit will still need to exist in cities of the future. Removing mass transit from city centers is probably going to happen; not by 2030, of course, but eventually. Today, I often see large, mostly empty buses and trains. We do that because we really don’t have an alternative, but we will soon. So, if mass transit is part of the long-term future, it will have to be radically redesigned for a completely new world. I certainly prefer the idea of personalized transit designed for the passengers, not the driver, with the capacity to enable a group travelling together to meet and socialize in comfort whilst travelling.

Kornik: It’s funny you say that because Los Angeles is part of a pilot program with the World Economic Forum to look at how to bring autonomous vehicles—flying taxis—to cities. Part of that plan is to make sure it is “mass transit” and not just for the super wealthy. What role do you see that playing in the future?

Wyatt: Whenever I see a city like that in a movie, it looks dreadful, and I certainly wouldn’t want to live there. To me, a pleasant city is one where it’s much easier to walk places or where you’ve got quiet electric vehicles that are personalized transport and optimized for full efficiency. I think the reason anyone is even considering flying vehicles—especially in a place like L.A.—is because it’s often too difficult to drive there so we need alternatives. So much of a city’s traffic is a consequence of the inefficiencies required to accommodate limitations of humans, as well as allowing for humans driving badly. It seems like flying taxis are going to be part of an urban future, but I’d rather look up and see sky, not traffic. I’m sure others feel differently, but for me the minute a city starts to feel chaotic, I start to look to a life in the country or by the sea. Now, I suppose if you happened to live right next to one of those superhighways I was talking about earlier, it could be horrific, I’ll admit. Still, probably no worse than living next to a seven-lane highway with lots of traffic today that runs through many cities. And it’ll be quieter. And cleaner. And some cities, I’m certain, with a little planning could find clever ways to hide those superhighways away.

Look at how Amazon delivers, particularly in big cities—the routes are completely optimized by computers. What they do with packages, we could do with people.

Urban planning on a whole new level: What are we to make of “instant cities”?

Urban planning on a whole new level: What are we to make of “instant cities”?

Urban planning on a whole new level: What are we to make of “instant cities”?

When it comes to urban planning, there’s nothing more urban and planned than so-called “instant cities,” or cities built by visionaries from scratch in strategic global locations. Frustrated with the limitations of today’s cities to address overcrowding, pollution and inequality, visionaries are pursuing instant cities, which tend to share the common ideals of creating connected, sustainable, inclusive and equitable societies, thereby providing residents with a life in balance.

Instant city developers seek renewable energy sources like solar and wind to reduce carbon emissions and counteract climate change. Similarly, they want to eliminate the need for cars and streets, and they lean heavily toward the construction of energy-saving green buildings. Using water more efficiently is an overarching theme, as is employing artificial intelligence to discover how day-to-day life and city services can be improved.

What follows is a brief overview of instant cities of note—two that are not yet built and two that are currently under development. The four cities with eccentric names—Telosa, Neom, Masdar City and Songdo—range from grand, bold and futuristic blueprints to projects that are still very much works in progress, as all cities are, to some extent.

Greg Lindsay, Senior Fellow at NewCities and a visiting scholar at New York University’s Ruden Center for Transportation Policy and Management, has been studying instant cities for more than a decade, and says he finds them fascinating on multiple levels. “One is the realization of just how hard it is to build a city,” Lindsay says. “It seems no matter how much time and effort a team of architects and engineers can put into it, they can never quite replicate that lived-in feeling.”

Lindsay says instant cities serve best as prototypes for what you can achieve by networking cutting-edge technologies into a unified system to see what’s possible. Songdo, for instance, has pneumatic tubes for waste collection and burns that into clean electricity.

But the larger problem is, as fast as these cities get built, they don't get built fast enough. “We call them instant cities, but when I visited Songdo there was sprawl all the way around the urban edge that popped up long before they ever even broke ground on the sustainable district,” Lindsay continues. “So, it underscores that urbanization is going to happen much faster than any of these prototype cities can solve.”

Frustrated with the limitations of today’s cities to address overcrowding, pollution and inequality, visionaries are pursuing instant cities, which tend to share the common ideals of creating connected, sustainable, inclusive and equitable societies, thereby providing residents with a life in balance.

Telosa

Telosa is a proposed instant city that promises to set “a global standard for urban living, expand human potential, and become a blueprint for future generations.” In a video introducing the project, Lore suggests that the growing income and wealth disparity is harming the quality of life in the U.S. As a built-from-scratch city, Telosa can reverse that trend, he continues, or at the very least provide a new societal model from which to learn.

The guiding principle behind Telosa’s economic system is Equitism, a concept in which residents share ownership in a city’s land and prosper along with the city. If a community endowment that was focused on improving the quality of life of residents owned all the land in Manhattan, the argument goes, it would be worth more than $1 trillion today. That would generate $60 billion a year in income to invest back into the community—about twice the current annual spending—to provide residents with the best services available.

Lore proposes to invest an initial $25 billion to develop 1,500 acres for a population of 50,000 residents, with the first of those moving in by 2030. Planners envision a total of population of 5 million in 40 years with 33 residents per acre, which is on par with San Francisco’s density.

Telosa at a glance:

Location: U.S. (Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Arizona, Texas and Appalachian region under consideration)

Cost: US$400 billion

Size: 150,000 acres

Visionary: Marc Lore, entrepreneur, former president and CEO of Walmart U.S. eCommerce

Status: Proposed

Masdar City

Construction of Masdar City began in February 2008 with the vision of bringing together residents, students, entrepreneurs, business leaders, investors and academics in a collaborative, innovative and green community. Located near the Abu Dhabi International Airport and 40 minutes from Dubai, Masdar City has attracted some 800 companies from six continents, the region’s first clean technology start-up accelerator, and a technology park built out of recycled shipping containers. In addition to several retailers and restaurants, amenities include parks with urban farming areas, a recreation path encircling the city, and sports and gym facilities.

About 1,300 people currently live in the city, and ambitious plans call for an underground “personal rapid transit” system of driverless pods that will move people throughout the city to keep streets free of cars. After initially being bankrolled by Mubadala Investment Co., Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, Masdar City is now attracting third-party investment.

Masdar City at a glance:

Location: United Arab Emirates

Cost: US$22 billion

Size: 2.3 square miles

Visionary: Mubadala Investment Company

Status: Work in progress

Songdo

Planners conceived Songdo IBD in 2001 on reclaimed land from the Yellow Sea and within the larger footprint of Songdo City. The master plan calls for an ideal mix of live-work-play environments, including 40 million square feet of commercial space, 10 million square feet of retail, and 35 million square feet of residential units. Some 40% of the acreage is reserved for public green space—primarily the Jack Nicklaus Golf Club Korea and a central park.

Construction began in 2005, and planners originally envisioned completion in 2015. But Songdo IBD remains under development, and the population remains lower than first envisioned by 2022. An estimated 1,600 domestic and global companies operate in Songdo IBD. The district has 20 million square feet of space that meets the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED standards, including an exhibit hall, a school, a residential tower and the Sheraton Incheon Hotel.

Songdo International Business District at a glance:

Location: Incheon, South Korea

Cost: US$35 billion

Size: 1,500 acres

Visionary: Collaboration between Incheon Municipal City, Gale International, and Posco Engineering & Construction

Status: Work in progress

Did you enjoy this content? For more like this, subscribe to the VISION by Protiviti newsletter.

Protiviti: Emerging technologies, IoT will impact just how smart cities become

Protiviti: Emerging technologies, IoT will impact just how smart cities become

Protiviti: Emerging technologies, IoT will impact just how smart cities become

The Internet of Things is a game-changer that is slowly—and sometimes not so slowly—transforming the modern world before our eyes. The IoT market is growing, and it’s only a matter of time when smart cities will be a grid of connected devices that communicate with each other in real time. They will have the power to provide humans, computers and entire systems with data designed to improve our lives in any number of ways. But all this connectivity could be a double-edged sword. VISION by Protiviti’s Editor-in-Chief Joe Kornik sat down with Protiviti’s Christine Livingston, Managing Director, Emerging Technologies – IoT, and Geoff Weathersby, Director within the same group, to discuss the future of smart cities, IoT, privacy and regulation.

Kornik: You both spend a lot of time thinking about emerging technologies. What’s the potential for smart cities? How “smart” can cities get and what could that mean for the future?

Livingston: When it comes to cities, we’ve already started to see many of those emerging technologies. The critical infrastructure that supports cities is being controlled and sustained by these connected devices. And that can mean things like your water supply, your power, your electricity, the traffic lights… all the infrastructure that enables these cities to operate. One of the things that's been interesting is, we can start to see those devices pivot to play multiple roles. For example, traffic lights or intersections may have devices that were installed to monitor traffic flow and accidents, but now they could be used to investigate crime. So, things that were installed for a single purpose are pivoting to a much larger scale of possibility.

Weathersby: You’re 100% right, and I think we'll see more of those multiple uses being applied as cities continue to mature and adopt more technology. I think, as Christine said, we’ll see that improved infrastructure creates more efficiencies on the maintenance and support side. Cities have apps now where residents can react in real time and report something, whether it’s a pothole or graffiti. Suddenly, there’s visibility, and a city can act in a much shorter time frame. That communication, ultimately, results in an improved customer experience for people in cities. That could mean real-time synching of traffic lights, resulting in less traffic. That’s one area ripe for change, I think; we’re going to see big changes to mobility in cities. On a smaller scale, look at smart parking meters where you pay with an app, for instance. But I think the real impact on consumers and individuals is going to be better access to information, which leads to a more seamless interaction with the city around you.

Kornik: You mentioned both utilities and mobility, two services that are impacted in a smart city. What are the key issues in those areas, and which of the two will impact city dwellers in a more significant way?

Weathersby: Well, I think the most visible one is going to be mobility, for sure. We take energy for granted, especially here in the United States. We hit that light switch, and we expect it to work. Most of us don't really care about the carbon emission footprint or the kilowatts we’re using every day, at least not now. We're going to see a lot of movement on sustainability, and we'll see that develop, certainly, over the next 10, 15 or 20 years. New builds are very conscious of this and are built to smart building standards, but in a city there’s a lot of retrofitting required. How do you turn a 150-year-old brownstone in Manhattan into a LEED-certified building without tearing it down? Well, same thing is true with mobility. How do we retrofit mobility in cities? You’ve seen some cities in Europe decide to just block off cars from certain areas of the city, and people will travel on scooters or bikes or in autonomous vehicles to get around. As far as the most visible and disruptive game changer, it’ll be mobility.

How do you turn a 150-year-old brownstone in Manhattan into a LEED-certified building without tearing it down? Well, same thing is true with mobility. How do we retrofit mobility in cities? [...] As far as the most visible and disruptive game changer, it’ll be mobility.

– Geoff Weathersby, Protiviti

Kornik: Are you confident city officials will be savvy enough to use all this data they’re gathering in the right way? And while we’re at it, aren’t there some privacy and cyber security concerns to consider?

Livingston: Absolutely. I think about things like the Colonial Pipeline attack or the Florida water supply security event earlier this year as examples. It’s not all that interesting to think about how your water or energy is delivered to your home. It’s easy for it to feel invisible; it’s not a concern until it is a concern. But once systems are connected, that introduces a certain amount of vulnerability, and that's where you start to see some of the security concerns. There needs to be intentional thought about what those devices are being deployed to do, and the potential impact if there's a bad actor. City officials must develop mitigation strategies and know how they are going to keep a city’s infrastructure up and running in the event of an attack. It's really important for officials to think through those contingency plans and how all that technology and those devices will be used.

Kornik: Seems to me that how that data is used and shared, specifically between the private and public sector, will be a big key to the success of smart cities. How do you see that public-private relationship playing out?

Livingston: I think we started to see some really interesting things happen in the data sharing space with COVID, actually. In March of last year, as you know, hospital systems and states started sharing the data they were seeing, the patients they were treating, the treatments they were providing. And there were a lot of concerns around sharing and transmitting that data, and also a lot of unprecedented cooperation between some of those agencies. So, I think it’s interesting that we've already started to solve some of those problems. The ethics of how you maintain individual citizens’ privacy while making the right information available to the right people at the right time is going to be interesting. I suspect we’ll see many passionate ethical debates on that.

Weathersby: I think you're right, Christine. We’re already starting to see some of that transparency bubble up. The recent Apple commercials have been addressing privacy, and three years ago hardly anyone was even talking about it. We've seen more awareness lately on the consumer side as they're becoming more familiar with just how much data is being shared. There’s going to be demands, as Christine said, to understand where that privacy line is so we don’t cross it. It's finding that balance between convenience and security. Everybody loves that an app can tell you if you’re going to arrive somewhere two minutes late, but nobody is really thinking about the data that app is collecting on every phone to provide that information. And Apple just announced a digital driver's license. All of these technologies are going to continue to evolve over the next 10 years, and I think there's a big cultural shift going on in cities. How do you keep that extended network secure? We’ve got connected, smart parking meters; how do officials make sure they don't become the breach into the overall network? So, it's not just the data cities are collecting; it’s being able to secure that large, integrated network that you need to make a city a smart city.

There needs to be intentional thought about what those devices are being deployed to do, and the potential impact if there's a bad actor. City officials must develop mitigation strategies and know how they are going to keep a city’s infrastructure up and running in the event of an attack. It's really important for officials to think through those contingency plans and how all that technology and devices will be used.

– Christine Livingston, Protiviti

Kornik: How do you see the regulatory environment evolving here in the United States as these technologies become more prevalent? Where is that headed?

Livingston: I think things are evolving so quickly; had you asked me this a year ago, or maybe even a month ago, the answer might have been different. And it will surely be different in the future. Look at some of the health data we're now collecting and monitoring just so someone can travel. Who knows where that ends up? And I think that's going to break down some of those long-standing barriers and expectations around data privacy, and what is and isn’t available to the government. And every state in the U.S. has different privacy laws and different regulations. There will be variability in how states communicate with the federal government. A lot of this has to do with the notion of consent and understanding what constitutes consent in certain scenarios. I think that landscape is rapidly shifting and was greatly accelerated by COVID, as were many other digital transformation efforts.

Kornik: I know it's difficult to look too far out into the future but give me your long-term vision of what a smart city might look like in 2030 and beyond?

Livingston: We’ve touched on the biggest one and it may come even before 2030, but I don't think you'll see very many individually owned vehicles in cities. In fact, you may not see any. And we know Amazon is already experimenting with new technology such as drones for delivery, and I don’t think that’s very far off at all.

Weathersby: If you drop a person into New York City or London or Tokyo in 2030, I think they’ll notice a few things: I think cities are going to be quieter. I think they're going to be cleaner. I think you're going to have a lot more electric and autonomous vehicles, and you're going to have more automation and more autonomous robot sensors. I think you're going to end up seeing a hybrid world where city officials will know in real time what needs to be maintained and when, and residents will experience a world of connected commercialism. You’ll get off the train, and you’ll get an alert that your favorite coffee shop has a franchise two doors down. Your daily life is going to become more seamless, much the way you get in your car today and your phone picks up Apple CarPlay or Android Auto, and your devices will pass along data about the world around you and your own behavior and patterns. That's what I think will be most noticeable in the future as we envision it here in 2021. However, it’ll be completely seamless and largely unnoticeable to those living in 2030.

Christine Livingston is Managing Director with Protiviti's Emerging Technology Group – Internet of Things.

Geoff Weathersby is Director with Protiviti's Emerging Technology Group.

Did you enjoy this content? For more like this, subscribe to the VISION by Protiviti newsletter.

The cities are alright: Yes, they’ll survive... and be far more important in 2030 and beyond

The cities are alright: Yes, they’ll survive... and be far more important in 2030 and beyond

The cities are alright: Yes, they’ll survive... and be far more important in 2030 and beyond

There’s some debate as to where and when the first cities on Earth began. Most scholars agree urbanization began in Mesopotamia in the Middle East about 10,000 years ago. It’s biggest city, Jericho, probably had about 3,000 people clustering together for survival. It was a few thousand years later that Uruk in present day Iraq emerged as a religious, cultural, and political center of influence for its 40,000-plus residents. Uruk, more than Jericho, often gets the distinction as Earth’s first “city” since it brought more to the table than the simple survival of the species.

Why this historical background on the origin of cities? Because it’s important to remember that cities as we know them today weren’t always here. We created them… with purpose. And that criteria of cities as centers of purpose and influence carries forward all the way to today.

Cities remain the cultural, political, creative and economic centers of influence. They are the heartbeat of humanity. Today, more than 4 billion people—more than half of the world’s population—reside in urban areas. By 2050, the United Nations estimates two-thirds of us will call cities home. By then, almost 7 billion of the estimated 10 billion people on Earth will live in cities. So yes, they are vastly important to the success of the planet and all the people who live on it. If our cities fail, we all fail.

This is why, when Protiviti decided to launch a global resource for the C-suite and boardroom focused on the transformational forces that would impact business in 2030 and beyond—VISION by Protiviti—the future of cities seemed like the perfect place to start.

Cities were facing significant challenges even before a global pandemic rocked them in a way they’ve never been rocked before. But 2020 saw residents fleeing urban areas en masse and businesses getting shuttered. Many offices anchored in central business districts remained empty as workers shifted to remote work. There was no shortage of “this is the end of cities” commentary out there. But are cities really dying?

We partnered with professors in the University of Oxford’s Sustainable Urban Development department to conduct an exclusive global survey of CEOs and executive board members to find the answers to this and other questions. Among the many key takeaways from the data, this one stands out: Despite all they’ve been through, a whopping 94% of CEOs believe cities will either be more important (64%) or as important (30%) to their overall strategy a decade from now.

These findings are significant and highly relevant. Cities may have bent, but they’re not broken. They’ve been pushed to their breaking point as waves of political, social, and economic upheaval subjected them to the ultimate stress test. And the verdict is in: They passed. From where we sit, reports of their demise have been greatly exaggerated.

As New York Comptroller Tom DiNapoli so eloquently states: “I think the city has the potential to be stronger than ever in 2030. New York has come through many crises over the years, including a pandemic, and our history as a city says that whenever we come through a crisis, we end up better, not worse.”

For this project, we interviewed more than 50 luminaries, futurists, physicists, strategists, executives, innovation officers, information officers, architects, urban planners, politicians, policy makers, professors, pundits, journalists, and other big thinkers outside our organization, as well as several of Protiviti’s own thought leaders and subject-matter experts. We asked them about the future of cities, and specifically, how that future would impact business over the next decade. The content created is the culmination of their insights representing perspectives from six continents.

When diving headfirst into the subject of cities, there are myriad aspects to consider. For this topic, we broadly explored technology and what are commonly called “smart cities,” infrastructure, sustainability and climate, leadership and the role both the public and private sector would play in cities’ future.

By 2050, the United Nations estimates two-thirds of us will call cities home. By then, almost 7 billion of the estimated 10 billion people on Earth will live in cities.

Technology and smart cities

Most cities are using cutting-edge technologies and AI sensors to track data in real time to enhance performance, service and user experience. But where we are now in terms of deployment is nowhere close to where we will be even a few years from now.

As Jonathan Reichental, Ph.D., Professor and smart cities expert says, “We’re looking at multi-trillions in new technology opportunities over the next decade and beyond.” Almost universally, most experts seem to think we’ll also see an abundance of electric vehicles and even some autonomous vehicles in cities by decade’s end. Mick Cornett, mayor of Oklahoma City from 2004-2018 says “a full integration of autonomous vehicles is probably more than a decade away, but when it does happen, it will have a profound effect on how cities function.” Many cities have already started to restrict automobiles in certain areas and personal mobility devices, such as scooters and e-bikes are on their way… perhaps even summoned by your phone or wristwatch. The revolution of personal electric mobility is really taking off in Europe, says Greg Lindsay, Futurist and Senior Fellow at New Cities. “More than 10% of households in Germany now have electric bicycles and forward-thinking cities like Paris, Milan, Madrid, and others offer personal subsidies for an e-bike or a scooter.”

And speaking of taking off, the FAA is expected to certify an urban air mobility aircraft in 2023 and if that goes well, many operators are looking to get their fleets off the ground in 2024, says Clint Harper, an Air Mobility Fellow with the City of Los Angeles, which is part of an air mobility pilot program with the World Economic Forum. Meanwhile, Petra Hurtado, Research Director for the American Planning Association, says she’s “confident flying taxis will be in the U.S. by 2028, sooner in Europe and Asia.”

But all this connectivity could come at a price, say Protiviti’s cybersecurity experts Scott Laliberte and Krissy Safi. There’s already been some pushback: In Toronto, where Google had planned to build its own smart city, residents complained that the level of surveillance was too invasive, says Ron Blatman, Executive Producer of Saving the City, a non-profit focused on city advocacy. Google pulled the plug in 2020.

And just as we begin to wrap our heads around the possibilities, it won’t long be at all before quantum computing and its mind-numbing capabilities change cities in ways most of us can’t imagine, says Protiviti’s Konstantinos Karagiannis.

Climate and Sustainability

Cities will survive but major changes are inevitable. To illustrate: In many ways, cities are the epicenter of the climate crisis. “By 2030, we’ll know what cities will be unlivable,” says Andrew Winston, a renowned sustainability strategist. “There are several places where we won’t be living in 40 or 50 years. Or at least not living the same way we do now.” Winston says he fears too many executives are unprepared for the coming climate crisis. “The executives I’ve spoken to clearly haven’t given much thought to what it will mean to conduct business in a climate-constrained world,” he says.

But some cities have already started the planning. In Indonesia, the government recently announced an ambitious plan to relocate the capital city due, in part, to environmental issues. By 2050, the United Nations estimates much of Jakarta will be under water, but that hasn’t stopped Jakarta’s MRT (Mass Rail Transit) from building the country’s first metro system.